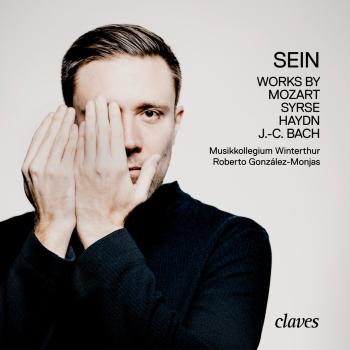

«Sein» works by Mozart - Syrse - Haydn - J.-C. Bach Roberto González-Monjas & Musikkollegium Winterthur

Album info

Album-Release:

2024

HRA-Release:

24.01.2025

Label: Claves Records

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Artist: Roberto González-Monjas & Musikkollegium Winterthur

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), Diana Syrse (1984)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791): Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550:

- 1 Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550: I. Allegro moderato 06:36

- 2 Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550: II. Andante 11:52

- 3 Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550: III. Menuetto 04:07

- 4 Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550: IV. Allegro assai 06:49

- Diana Syrse (b. 1984): Quetzalcóatl for Orchestra:

- 5 Syrse: Quetzalcóatl for Orchestra 13:01

- Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 - 1809): Symphony No. 49 in F Minor, Hob I:49 "La passione":

- 6 Haydn: Symphony No. 49 in F Minor, Hob I:49 "La passione": I. Adagio 10:15

- 7 Haydn: Symphony No. 49 in F minor, Hob I:49 "La passione": II. Allegro di molto 06:33

- 8 Haydn: Symphony No. 49 in F minor, Hob I:49 "La passione": III. Minuet 05:01

- 9 Haydn: Symphony No. 49 in F minor, Hob I:49 "La passione": IV. Finale. Presto 03:22

- Johann Christian Bach (1735 - 1782): Symphony in G Miinor, Op. 6/6:

- 10 Bach: Symphony in G Miinor, Op. 6/6: I. Allegro 03:16

- 11 Bach: Symphony in G Minor, Op. 6/6: II. Andante più tosto Adagio 04:07

- 12 Bach: Symphony in G Minor, Op. 6/6: III. Allegro molto 02:23

Info for «Sein» works by Mozart - Syrse - Haydn - J.-C. Bach

The Musikkollegium Winterthur’s Chief Conductor, Roberto González-Monjas, took the three last symphonies that Mozart composed – in rapid succession in the summer of 1788 – as the inspiration for this large-scale seasonal triptych. While the first symphony (No. 39) in E flat major has a slow introduction, the last (No. 41), known as the “Jupiter Symphony”, ends with a breath-taking finale, so that “beginning” and “ending” – yes, let’s say “becoming” and “transcending” – are integral to the artistic concept of this trilogy. The central G minor Symphony (No. 40) stands for “being”: for “being in the centre.”

In fact, we are rarely thrown into a musical maelstrom as abruptly and breathlessly as in this G minor symphony by Mozart. It’s almost as if we notice the first, soft strains of the viola only when the violins make their entrance with their famous melody – and by that time, we have already been thrown into the thick of it. The fact that the melody became a mobile phone ringtone in the 1990s obscures how unusual it actually is: restless, consisting of small elements – “sighs,” as we often read.

The history of a sigh

For his time, the way Mozart uses these sighs is quite audacious. There is an established tradition of the poignant half-step friction between the notes E flat and D flat, between the minor sixth and fifth of the key. In his St Matthew Passion, for example, Johann Sebastian Bach uses minor sixths and fifths in an alto aria to express the words of the text “Buss und Reu.” And Mozart himself also likes to use this musical formula – when Barbarina sings her sorrowful cavatina in Le Nozze di Figaro, for instance. Yet in all these cases, the minor sixth so characteristic of minor keys is merely heard as an evasion; starting from the chordal fifth, it is briefly and expressively touched upon. In his Symphony No. 40, however, Mozart introduces the lugubrious sixth before the fifth is even heard! This, too, is an aspect of “being in the centre.”

This brief digression into the history of this musical formula of pain may make it clear that, in this case, the familiar form of the symphony is already operating with the aesthetic categories of discord and passion favoured by the literary epoch of “Sturm und Drang.” This aesthetic becomes even more striking in the abrupt final movement, which is characterised by caesuras. “Sighs and dissonances, daring modulations and chiaroscuro contrasts” are among the characteristics that Roberto González-Monjas mentions. The choice of G minor is also relevant in this context: in The Magic Flute, Pamina sings her “Ach ich fühl’s, es ist verschwunden” in this key. And Don Giovanni descends to hell in the key of G minor. As far as symphonies go, Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 is the culmination of a series of similarly agitated predecessors, such as Johann Christian Bach’s Symphony in G minor op. 6/6. In comparison, Mozart’s music is more obsessive – for example, in that the sighing figure is incessantly repeated, as if the music were touching a vexatious wound – and at the same time more rational, insofar as it is composed with unrivalled mastery.

Human failings

The fact that, even behind the expressive eccentricity, there is a planned concept reveals Mozart as an artist of the Enlightenment – also here in G minor, and not only in the work’s lighter sister symphonies in the keys of E flat and C major. For Roberto González-Monjas, however, Mozart succeeds in demonstrating this even more comprehensively than rationalist aesthetics – with their ideal of symmetry and perfection – would be capable of doing. Mozart is not afraid of showing “the wrinkles, even ugliness; the small and large failings that make us human.”

Roberto González-Monjas identifies “suffering” as the fundamental idea behind Mozart’s Symphony No. 40. But it is not merely “suffering in today’s parlance of pain and grief, but in the broader context of the 18th century, where everything that happens to us that we are unable to direct or control tends to be referred to in this way. González-Monjas is thinking of the physical – from twitching, dancing feet to carnal sin – and of course the broad field of emotions. It is no coincidence that in Mozart’s century, such sensations were referred to as “passions.”

Swept away in a “storm of passions”

Understood in this way, “suffering” becomes almost synonymous with “being.” And what art is better suited not only to reveal to us all the facets of existence, but also to make us suffer through them? Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 achieves this best when the music – such as the initial, sighing figure – appears in an ever-changing light, in ever-changing guises, as the movements progress. Sometimes surprisingly, sometimes logically. Mozart achieves what Johann Georg Sulzer wrote about listening to music in his Allgemeine Theorie der Schönen Künste (1771): “We feel a storm of passion that sweeps us away – and to which the soul is incapable of resisting.” (Felix Michel)

Musikkollegium Winterthur

Roberto González-Monjas,

violin, direction

Roberto González-Monjas

is an extremely sought-after conductor and violinist who has rapidly established an international reputation. He is Chief Conductor of the Musikkollegium Winterthur, Principal Guest Conductor of the Belgian National Orchestra as well as Chief Conductor of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia in Spain. As of September 2024, he will also be Chief Conductor of the Mozarteumorchester Salzburg. As a committed educator, Roberto González-Monjas founded the Iberacademy together with conductor Alejandro Posada in 2013. The institution aims to create an efficient and sustainable model of musical education in Latin America that focuses on disadvantaged sections of the population – as well as promoting highly talented young musicians. González-Monjas is also Professor of Violin at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, and regularly mentors and conducts the Guildhall School Chamber and Symphony Orchestra at London’s Barbican Hall. Previously, Roberto González-Monjas held the post of Concertmaster of the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia for six years and was also Concertmaster of the Musikkollegium Winterthur until the end of the 2020/21 season.

Booklet for «Sein» works by Mozart - Syrse - Haydn - J.-C. Bach