Sviatoslav Richter

Biographie Sviatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Richter

Richter’s father was a pianist and composer who had studied in Vienna and then taught at the Odessa Conservatory. He was German, and Richter’s mother was his pupil. The boy was raised in an artistic environment, but from the age of four until he was seven, he lived with his aunt. When he returned to Odessa he began piano lessons, but his natural musical curiosity and talent led to him sight-reading operatic scores and learning empirically. To earn money, from the age of fifteen to seventeen he was accompanist at the House of Sailors in Odessa, then made his solo debut and became accompanist to the Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre.

Largely self-taught, Richter was twenty-two when he entered the Moscow Conservatory where he studied with Heinrich Neuhaus. At his adult debut he played works by Prokofiev including the first performance of the Piano Sonata No. 6 Op. 82. He became friends with Prokofiev and gave the première of the Piano Sonata No. 7 Op. 83 in 1943; the Piano Sonata No. 9 Op. 103 was dedicated to him.

During World War II, Richter’s father (as a German) was arrested and executed, but at the end of the war his mother married her dead husband’s brother and settled in Stuttgart. However her son, thinking she had died during the war, did not see her again until 1961. Richter won joint first prize at the All-Union Piano Competition in Moscow and soon earned a reputation in the USSR in the years after the war. His first appearance outside of the USSR was at the Prague Spring Festival and the following year he played in China. However, it was not until 1960 that he travelled to the West, causing a sensation with his playing. In October of that year he gave no less than five recitals at Carnegie Hall within twelve days.

For the next thirty years Richter gave concerts throughout Europe and Japan. It was in 1964 that he founded a festival at the Grange de Meslay at Tours in France, where chamber music concerts were given in a converted barn. Favourite colleagues who regularly took part included violinist Oleg Kagan and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. During the 1970s and 1980s Richter became famous for cancelling concert appearances due to depression and ill health, and towards the end of his career preferred to use the score and minimal lighting during performances, also showing a preference for playing in small halls.

One of Richter’s great gifts was to be able to reveal the structure of a large work as if he was laying it out before his audience. His grasp and understanding of a work was uncompromising whether it was by Bach or Saint-Saëns, Schubert or Gershwin. Richter’s technique was legendary, as was his vast repertoire. His enormous talent seemed to encompass all styles and he was equally at home in Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Chopin and Liszt as well as the Russians and twentieth-century music by Bartók, Berg, Debussy, Szymanowski, Webern and Hindemith. Playing from the score during the 1980s enabled him to perform a huge amount of music that he would not have been able to learn from memory. Throughout his career he was not unduly concerned by the quality of the pianos made available to him, and the sound he produced could have a shallow tone.

An extremely complex individual, Richter was a unique personality and musician who lived by his own rules, unencumbered by influences of daily life. Apparently, he never taught the piano, but he enjoyed painting and exhibited works at the Pushkin Museum in 1978. Whether his performing career gave him satisfaction or joy is hard to know. At the end of an excellent two-and-a-half-hour television documentary by Bruno Monsaingeon, Richter says, ‘I do not like myself: that’s it.’ He remains, however, one of the truly great pianists of the twentieth century.

With an artist of Richter’s quality, and his huge following of admirers, it is no surprise to find a large number of recordings available from many sources including live performances and radio broadcasts. With such a long, busy career and a vast repertoire, there is a multitude of recordings issued by a myriad labels. Early recordings from the 1950s include extraordinary live performances of twelve Scriabin études from 1952. These were included in a ten-disc set from Melodya/BMG of recordings made between 1948 and 1973. A group of eight of Liszt’s Études d’exécution transcendante recorded during a performance in 1946 (or 1951) has had limited release but represents some of the most extraordinary piano playing ever captured by the microphone with the Étude in F minor given a terrifying performance. Richter’s Carnegie Hall concerts in 1960 were recorded and issued on LP by Columbia. However, these were soon withdrawn at Richter’s request and have become collector’s items. From 1972 comes a Scriabin recital given in Warsaw where Richter gives extraordinary performances of three sonatas, six études and twenty-four of the préludes. Other notable live recordings have been issued by Stradivarius whilst TNC/Cambria have issued no less than sixteen volumes of live performances in Kiev. From Philips comes a twenty-one-CD set entitled The Authorised Recordings whilst Olympia issued thirteen CDs of Richter’s playing. Pyramid have issued some of the Meslay performances whilst IMG/BBC Legends have issued a number of broadcast recordings from the Aldeburgh Festival and London, including both Liszt piano concertos from 1961 with the London Symphony Orchestra and Kyrill Kondrashin which were recorded for Philips at the same time.

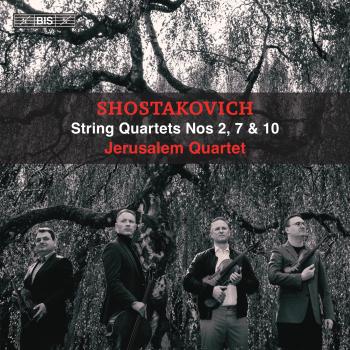

There are many commercial recordings that must be mentioned including Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor Op. 18 with Stanislav Wislocki and the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra in 1959 and a superlative live performance of Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 5 Op. 53 from 1963, one of the best on record. A legendary live recital recording was made in 1958 in Sofia and issued by Philips. Richter plays Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition as well as stunning performances of Liszt’s études, Harmonies du soir and Feux follets. It is an impossible task to mention every outstanding Richter recording but recordings of the Beethoven sonatas, Bach’s Das wohltemperierte Klavier, Schubert sonatas, Schumann’s Fantasie Op. 17 and Bunte Blätter Op. 99 and Liszt’s Piano Sonata all deserve mention. There is also a large quantity of recordings of Richter in chamber music with his friends including Benjamin Britten, Mstislav Rostropovich and Oleg Kagan.