Vienna State Opera Orchestra and Chorus & Hermann Scherchen

Biography Vienna State Opera Orchestra and Chorus & Hermann Scherchen

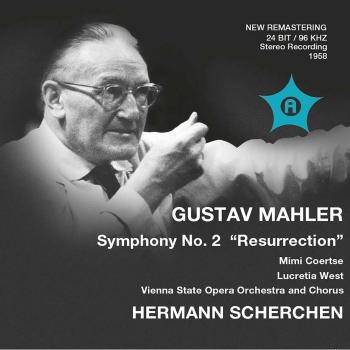

Hermann Scherchen

Largely self-taught as a musician, Hermann Scherchen joined the Blüthner Orchestra as a viola player in 1907, and played with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from 1907 to 1910. A performance in 1911 of Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 under Oskar Fried, in which he participated with the Blüthner Orchestra, left a deep impression. During the same year he assisted Schoenberg in the preparation for performance of Pierrot Lunaire, and made his debut conducting this work on the tour that followed its first performance in Berlin. Scherchen conducted Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 in Berlin in 1914, the year in which he was appointed conductor of the Riga Symphony Orchestra; however, following the outbreak of World War I he was interned and remained in Riga throughout the war. During this period of enforced confinement he learnt Russian, taught and composed.

Following his return to Berlin in 1918 Scherchen quickly became active in several different but related fields: he formed the Scherchen Quartet, directed a workers’ choir, founded the New Music Association (Neue Musikgesellschaft), and from 1919 published the radical musical magazine Melos. He was appointed conductor of the Grotrian-Steinweg Orchestra of the Leipzig Konzertverein in 1921, and in the following year both succeeded Wilhelm Furtwängler as conductor of the Museum Concerts in Frankfurt and became conductor of the Winterthur Musikkollegium in Switzerland. Following the formation of the International Society for Contemporary Music in 1923 Scherchen appeared regularly at its festivals of new music, directing an amazing number and variety of new works. He appeared as a guest conductor throughout Europe, and especially in London, during the 1920s and 1930s: in 1936 he conducted the world première of Berg’s Violin Concerto, in Barcelona. In addition he edited the new music journal Ars Viva between 1933 and 1936 and taught regularly. In 1928 Scherchen was appointed chief conductor of the East German Radio Orchestra at Königsberg, becoming principal conductor in 1931. As a convinced anti-fascist, he left Germany in 1933 following the assumption of power by the National Socialist Party, and settled in Switzerland where he lived for the rest of his life.

During World War II Scherchen remained active as a conductor, performing regularly in Switzerland (between 1944 and 1950 he was chief conductor of the Zürich Radio Orchestra) and occasionally in Greece. Thus after the end of the war he was well placed for new opportunities: however although he was offered the positions of conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus and Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestras, and of the Berlin State Opera, as well as the directorship of the Leipzig Conservatory, he turned them all down. In 1950 he suffered a series of personal and professional reverses, some of the latter being associated with his life-long support for socialist ideas, which almost drove him to suicide. Fortunately he soon met his future fifth wife, Pia Andronescu, by whom he was to have five children, and professionally he began his long association with the Westminster record company, maintaining this until 1965, when the company suffered a severe financial crisis. The recordings which he made for Westminster established his name internationally.

During the 1950s and 1960s Scherchen appeared once again as a guest conductor in Europe, frequently conducting programmes of challenging or new music: his direction of Schoenberg’s opera Moses und Aron in Berlin in 1959 was of central importance in promoting this work internationally. In addition he taught conducting in Venice and Darmstadt and founded the Ars Viva imprint for the publication of new music. His final permanent appointment lasted only for one year, between 1959 and 1960, when he served as chief conductor of the North West German Philharmonic Orchestra, Herford. Scherchen did not make his American debut until 1964, when he conducted in Philadelphia and New York, despite by then being extremely well known through his recordings. He died several days after conducting Malipiero’s L’Orfeide in Florence.

Scherchen was a figure of central importance in twentieth-century musical life, his continuing espousal of new music making him one of its foremost proponents in Europe. As a conductor he held a deep respect for the composer’s written text, for instance seeking to perform Beethoven’s symphonies at the tempi indicated in the manuscripts, an unusual practice for the time. Technically he believed that a conductor should commence work with an orchestra only when every aspect of a score had been completely memorised, and could be rehearsed from memory. Film of Scherchen conducting shows him to have possessed a very simple and clear beat. Yet he could summon up performances of raw power as well as of great character. He saw the conductor’s job very much as animating the music beyond the notes, writing in 1935, ‘A music devoid of any emotion, of any aesthetic pleasure or spiritual clarification may be of interest to the professional, but has no meaning whatsoever to the normal listener.’

His recorded legacy consists of numerous commercial as well as radio recordings. Virtually every performance that he conducted, whatever the circumstances, was of interest. To quote the producer of many of his Westminster recordings, Dr Kurt List: ‘With Scherchen the result is never boring, nor does it leave you indifferent. If you think of the many colourless conductors around the world, I believe that one has to take Scherchen as he is: a voluntarily personal stylist who nevertheless always throws an interesting light on things, even if this light is wrong!’ In many ways Scherchen, through his insistence upon fidelity to the text, foreshadowed the period performance practice movement of the end of the twentieth century. His recordings of music by Bach, Handel, Haydn, Beethoven, Berlioz and Mahler remain important milestones in the history of recorded music, as do those of music by composers who were his contemporaries such as Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. He saw music as a living continuum between the old and the new, which he sought to bring together as often as possible.