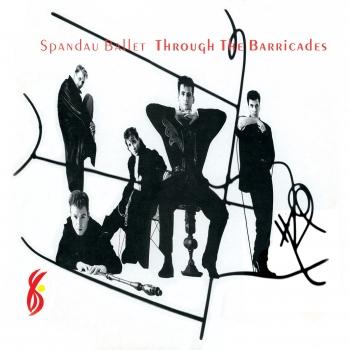

Spandau Ballet

Biography Spandau Ballet

Spandau Ballet

The first time that most Londoners heard the words Spandau Ballet was on the London Weekend Television arts programme Twentieth Century Box, in May 1980. Presented by Danny Baker, Twentieth Century Box was the place you went to for your youth culture fix.

And Baker’s programme was devoted to a new cult, The Cult With No Name, a bunch of soul boys and girls, disaffected art students, hairdressers and apprentice advertising salesman who all wore clothes that referenced architecture rather than pop culture, and who frequented the most elite Soho nightclubs, and who learned the art of reinvention at the knee of David Bowie.

Elegant, well dressed, and rather bizarrely obsessed with cleanliness (the band were quoted on the show saying that they hated most gigs because everyone was so dirty), they were, to put a fine point on it, the In Crowd.

And Spandau Ballet were the In Crowd’s band. Ushering in a new era of visually-dominated pop, their dissatisfaction with their musical peers manifested itself in a mechanical, stylised sound that was born and bred on the dancefloor’s of the West End. They were Bowie Kids, Blitz Kids, white soul boys who had rejected funk and rock while embracing electronica, frilly shirts and tuxedos.

Amateurish? Ridiculous? Their adolescent pretensions represented a sensibility rather than a display of ability. “We’re not just another band,” said the band’s singer Tony Hadley. And they weren’t, not by the longest piece of chalk in town. Although, they were soon to become one of Britain’s biggest bands.

The surface smarts and radio-friendly sheen of Spandau Ballet’s biggest, most pervasive hits are familiar to anyone in possession of a radio or a laptop, anyone who was born in the last 50 years or indeed anyone who regularly goes to the movies or watches television – the group’s songs have been used in the Simpsons, Spin City, Charlie’s Angels, The Wedding Singer and Ugly Betty, as well as in advertisements for Coca Cola, Sony Ericsson, Caixa, Nissan, Nescafe, Pils and dozens more – while the band’s songs have been covered by everyone from the Black Eyed Peas and Nelly to Paul Anka and Lloyd & Lil Wayne.

Not only that, but the earlier, more club-orientated Spandau tracks were some of the most exciting records of the early Eighties – in their time as fresh, as intoxicating and as brash as anything produced by their after-dark contemporaries. When discussing the pantheon of Eighties pop, Spandau have occasionally been ignored, but their early records remain some of the most influential, and some of the most resonant of the period. As anyone who was there can tell you.

At the time of their birth, in 1979, the idea of cool – genuine cool – was often less about the music and more – far more – about being in the right place at the right time. It is impossible to stress too highly how achingly fashionable Spandau Ballet were in the winter of 1979 and the summer of 1980 (“so hip it hurt,” the papers said at the time). On the evening of July 26th 1980 there were few places more fashionable to be than on HMS Belfast, watching Spandau Ballet effortlessly career through their set. But although Spandau were the most fashionable band of their time, it wasn’t all about fashion. The music mattered. A lot. Bravely – well, brave in context – the band decided to launch themselves on audiences who were far more comfortable dancing to records by the likes of Kraftwerk, Bowie, Sparks and Telex, and they successfully played gigs at the Blitz nightclub, at London’s Scala Cinema (at the time the most fashionable venue in town), the Botanical Gardens in Birmingham, the Underground Club in New York, the Papgayo in St Tropez, and of course the infamous Ku Club in Ibiza (a decade before it became the trendy destination du jour). And it worked. Like all decent phenomena, having created a huge buzz on the club scene, the band were involved in a major bidding war, eventually signing to Chrysalis Records and releasing the classic “To Cut a Long Story Short”, produced by Richard James Burgess.

With Spandau, the music was not only timely, it was groundbreaking. Prescient, even. Of the moment. And unnerving to anyone not in the know. “To Cut A Long Story Short” was an era-defining slice of electronic myth-making, and a great dance record to boot (if it hadn’t been, the cognoscenti, those who went to the same clubs as Spandau, would have strangled it at birth – or, more pertinently, refused to dance to it); “Musclebound” was a clever, seductive spin on body politics; and “Chant No.1 (We Don’t Need This Pressure On)” was, in its own way, as important to the summer of 1981 as “Ghost Town” by the Specials – a canny mix of contemporary funk and bottom-heavy agitprop, the perfect encapsulation of the new decade’s obsession with fiddling while Brixton and Toxteth burned. It is one of the most important records of the early Eighties, and this is not an opinion solely justified by hindsight.

Having come fully-formed from the new romantic Billy’s/Blitz club scene, Spandau completely understood the currency of the dancefloor, and one of their innovations was to issue every single in a remixed 12” format, stealing a march on their competitors in the charts, and giving them prime equity in nightclubs from Canvey Island to New Jersey, from Soho to SoHo. And back again.

In this respect Spandau didn’t so much surf the zeitgeist as kick-start the wave. And soon they were spearheading an era of new pop that was destined to traverse the globe. Along with Duran Duran, Sade, Culture Club and Wham!, as well as dozens of other British groups who grew out of the new romantic scene at the end of the Seventies, by the mid Eighties Spandau were global superstars, exponents of a shiny, unapologetic riposte to the post-punk industrialists and the emerging left-of-centre political independents celebrated by the NME (who hated Spandau because they could never get into the nightclubs where they were playing). Spandau became poster boys of designer pop, and their regular appearances in magazines such as i-D, The Face, Blitz and New Sounds New Styles helped turn them into copper-bottomed bold-face names. Then, with worldwide blue-eyed soul hits such as “True”, “Gold”, “Communication” and “Lifeline” the band achieved rather iconic status, and in the space of two years went from playing trendy nightclubs to playing stadia all over the world. The release of their third album True, in 1983, heralded a slicker, more adult contemporary sound, produced by Tony Swain and Steve Jolley, the title track being an homage to, amongst other things, Marvin Gaye (in 1991, P.M. Dawn sampled the song brilliantly in “Set Adrift On Memory Bliss”, which became a huge global hit). Around this time Spandau’s club-centric image changed too, and they swapped their harsh new romantic threads for smart, expensive, tailored pastel suits, exactly at the same time as David Bowie – who, on his Serious Moonlight tour in 1983, could easily have been the sixth member of Spandau. Steered by their manager Steve Dagger (a Peter Grant for the post-punk world)Spandau became one of the most commercially successful bands of the Eighties, and during their career they notched up 23 hit singles and spent a combined total of in excess of 500 weeks in the UK charts, and achieved album sales of over 25 million worldwide. Some of their songs, like “True”, “Gold” and “Through the Barricades” (karaoke favourites all), have become standards, while “True” has now achieved almost four million plays in North America alone. Not only that, but it is impossible to watch a televised sporting event these days without hearing “Gold” on heavy rotation.

The group’s enormous success was rubber-stamped by their appearance on the historic Band Aid record and by their performance at Live Aid at Wembley Stadium in the summer of 1985 – not only the most important concert of the Eighties, not only the biggest gig of all time, but also the consummate socio-political flashpoint: never had global awareness been channelled in such a way.

Since splitting up at the end of the Eighties, after a decade of unparalleled success, the Kemps established themselves as credible actors in The Krays, with Gary going on to star in the Whitney Houston vehicle The Bodyguard, and Martin becoming a household name and Britain’s most popular actor in the BBC’s EastEnders.

Tony Hadley embarked on a successful solo recording career, starred as Billy Flynn in the West End production of Chicago and won ITV’s reality TV show Reborn In The USA.

Steve Norman has stayed true to Spandau’s dance credentials, immersing himself in the house music scene for the last decade. Releasing tunes with his band Cloudfish, he also plays live sax in various super clubs around the world in collaboration with DJs.

And John has never erred from his passion for, in his own words, “hitting things with other things,” for various artists including Tony Hadley.

Spandau Ballet lasted ten years, a career arc that spanned the Eighties in perfect symmetry, from the nightclubs of Soho and Ibiza to Hollywood and the stadiums of Europe and Australia. Along with the other bastions of New Pop, Spandau Ballet defined the decade – proving, perhaps, that eyeliner, tartan capes and the variances of the Linn drum are not necessarily mutually exclusive. They came, they saw, they partied. And then they left, leaving a good-looking legacy.