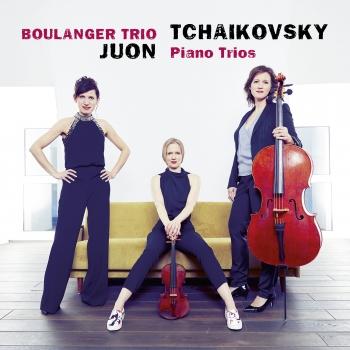

Teach Me! (The Students of Nadia Boulanger) Boulanger Trio

Album info

Album-Release:

2021

HRA-Release:

05.03.2021

Album including Album cover

- Jean Françaix (1912 - 1997): Trio pour violon, violoncelle et piano (1986):

- 1 Trio pour violon, violoncelle et piano (1986): I. - 03:44

- 2 Trio pour violon, violoncelle et piano (1986): II. Scherzando 04:19

- 3 Trio pour violon, violoncelle et piano (1986): III. Andante 04:58

- 4 Trio pour violon, violoncelle et piano (1986): IV. Allegrissimo 04:53

- Leonard Bernstein (1918 - 1990):

- 5 West Side Story: Maria. Slowly and freely - Moderato con Anima 03:05

- Aaron Copland (1900 - 1990):

- 6 Vitebsk - Study a Jewish Theme (1929) 11:40

- Philip Glass (b. 1937):

- 7 Head On (1967) 03:21

- Astor Piazzolla (1921 - 1992): Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas:

- 8 Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: Primavera Porteña 04:42

- 9 Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: Verano Porteño 07:31

- 10 Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: Otoño Porteño 05:29

- 11 Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas: Invierno Porteño 06:56

- Quincy Jones (b. 1933):

- 12 Main Title from The Color Purple 05:20

Info for Teach Me! (The Students of Nadia Boulanger)

Nadia Boulanger, or: Teaching as a Relationship

“I was accustomed to say that the composer must look far ahead into the future of his music. This seems to me to be the male train of thought: thinking at once of the whole future, of the entire fate of the idea, and preparing himself in advance for every possible eventuality. This is the manner in which a man builds his house, orders his affairs and arms himself for his wars. The other is the woman’s way of looking at the world, using good powers of judgement to address the immediate consequences of a problem, while failing to allow for more distant events. This is the approach of the seamstress, who could work with the most luxurious fabric, without thinking about how long it will last, provided it achieves the desired effect at the present moment. It need last no longer than the fashion. This is the approach of the kind of cook who prepares a salad without asking herself whether all the ingredients are right and go together well, whether they combine satisfactorily. A French sauce - or perhaps a Franco-Russian one - is poured over it and so everything is blended. Composing to such directions is consequently nothing but the production of a certain style.” (Der Segen der Sauce, p. 150)

Arnold Schoenberg directed his 1948 polemic against an unknown person of the feminine gender. He undoubtedly meant Nadia Boulanger. There were no other female teachers of composition at that time, her ancestry was Franco-Russian, and her work with Schoenberg’s polar opposite, Igor Stravinsky, was Franco-Russian too.

More than seventy years have passed since Schoenberg's chauvinist pronouncement, and the question of what can be considered innovative and what not, and by what standards, is differently worded today. And the assessment of the various forms of music associated with Nadia Boulanger will vary with one’s aesthetic standpoint.

The name of Nadia Boulanger is linked in the history of music with neoclassicism and in particular with Igor Stravinsky. A glance at her student lists will nevertheless be sufficient to show that in her sixty years and more as a teacher, she gave instruction to pupils of very different backgrounds. Her student body was decidedly international and covered a wide spectrum of styles, from the works of a champion of American modernism, Elliott Carter, by way of the “practical music” of Aaron Copland and his like to the tangos of Astor Piazzolla, from the musique concrète of Pierre Schaeffer by way of the neoclassicist style of Jean Francaix to the pop music of Quincy Jones and the film scores of Michel Legrand. She taught many women too, among them the Turkish composer Idil Biret, the Englishwoman Thea Musgrave, the American Marion Bauer and the Pole Grazyna Bacewicz. There is thus no justification for talking of a Boulanger school in the sense of a particular style. There was the term “Boulangerie”, an affectionately ironic play on words to describe pupils and friends of Nadia Boulanger, but it is a term that suggests a particular spirit, rather than a style.

The source material on her teaching is mostly drawn from a rich fund of reminiscences: numerous pupils, along with friends such as Leonard Bernstein or Yehudi Menuhin, have sought to describe what actually made Nadia Boulanger capable of pointing the way forward over many decades to young musicians from all over the world. This is both a question of her extensive knowledge, her incomparable ear for music (Yehudi Menuhin) and the way she “thought in notes” (Igor Markevich), and a matter of her enthousiasme and rigueur (Paul Valéry), a “special blend of energy and attention” (Antoine Terrasse) and “French intellect and Russian soul” (Yehudi Menuhin). Common to all who gave such testimony is the fact that they are describing the personality of their teacher rather than the conduct of her lessons, as noted by Lennox Berkeley, one of Nadia Boulanger’s first English pupils in the 1920s:

“I have often been asked how the fame of Nadia Boulanger as a teacher is to be explained, how she could have enjoyed so much success in leading young composers to their own musical language and what methods she used. I would say that she never used a particular method; other than the conventional instruction in harmony, counterpoint and instrumentation. She distrusted all musical systems. In fact it was the force of her personality and the example that she set with her life, which was totally concentrated on music, that exerted such an uplifting influence. She inspired us, she conveyed to us an awareness of the necessity to form a compositional technique of one’s own, for which no effort was too great. Apart from that, she insisted upon a knowledge of past composers, and on this basis she helped us to develop a sense of form. Her lessons in analysis were memorable […].” (Mademoiselle, p. 124)

Nadia Boulanger left behind no great number of compositions, nor did she write an introduction to harmony or composition, even though these are the publications that chiefly establish the authority of a composition teacher. Her oeuvre took shape during her lessons, in conversation, in animated exchange with her students:

“Nadia Boulanger impressed one with a quite special blend of energy and attention. Without any hidden meaning, the charm that she radiated was a mixture of male and female elements. She bore herself quite erect, her movements were full of elegance, her gaze exceptionally vivid. It was a look that was always ready to take an interest, whether it was a matter of amazement or delight. Yes, a rare mixture of power, intelligence and a controlled sensitivity. In all this she showed absolute self-control. [...] Even those who were not her pupils are well aware that her mode of teaching was also a dialogue, a sharing. She needed to create an encounter, provoke an awakening. That was not always to be achieved without difficulty; between such an intellect and students who were intimidated or daunted by such a challenge, embarrassing situations could easily develop. In those moments, Nadia Boulanger applied all the resources of her intelligence, open to all questions and alert for the deepest misgivings. Then, through an astonishing retreat, the mastery which she seemed destined to assert triggered an effort of will in her conversational partner and prompted that learner to give what was most true in himself or herself.” (Antoine Terrasse, p. 53)

Nadia Boulanger’s art of instruction was thus also the expression of an art of relationship anchored in the moment, unrepeatable and incapable of being fixed in writing. This offers a structural parallel to the function of the salon so crucial to the history of French culture. To ensure the desired intimacy, the number of participants was limited and made dependent on the satisfaction of certain criteria, such as a high level of education and membership of a higher social class. Exclusivity is very important in this connexion. The initiates knew each other, met regularly over the years, were driven by the same ideas. The Paris salons were centres of a highly developed urban culture and in many respects set the pattern upon which Nadia Boulanger consciously or unconsciously modelled her teaching and the environment in which it took place. Admission to her celebrated analysis classes, which took place every Wednesday afternoon in her apartment in the Rue Ballu in Montmartre, was by invitation only. No payment was requested or accepted for these lessons, although Nadia Boulanger made her living by teaching. After the group instruction, tea was served, and the students engaged in discussion with guests, composers among them, but often writers, philosophers, painters as well.

To return to Arnold Schoenberg’s polemical utterance quoted earlier: there can be no question of “directions”, nor of a “certain style”, still less of the “production” of a particular style in the case of Nadia Boulanger; but one can very well talk of a way of thinking and working that bears the cultural connotation of “feminine” - albeit, otherwise than supposed by Schoenberg, in a positive sense. What is more, developments since 1989 have shown that Nadia Boulanger looked very far into the future.

Boulanger Trio

Boulanger Trio

The German newspaper Die Welt described a performance of the Boulanger Trio as “irresistible”, while Wolfgang Rihm wrote in a letter: “To be interpreted in this way is surely the great dream of every composer.”

Formed in Hamburg in 2006 by Karla Haltenwanger (piano), Birgit Erz (violin) and Ilona Kindt (cello), the trio is now based in Berlin. Already in 2007 the ensemble won the 4th Trondheim International Chamber Music Competition in Norway, followed by the Rauhe Prize for Modern Chamber Music in 2008. The ensemble has received crucial musical guidance from Hatto Beyerle, Menahem Pressler and Alfred Brendel.

In the past years, the trio has gained an excellent reputation in the world of chamber music, and it was invited to prestigious venues such as Konzerthaus Berlin, Festspielhaus Baden‐Baden, Palais des Beaux Arts Brussels, Wigmore Hall London and Philharmonie Berlin. The musicians also regularly appear at festivals like the Schleswig‐Holstein Musik Festival, the Heidelberger Frühling, the Dialoge at Mozarteum Salzburg, Ultraschall in Berlin and the Sommerliche Musiktage Hitzacker.

In addition to works of the classical and romantic period, the commitment to contemporary music is an important focus within the trio’s repertoire. The ensemble is collaborating with some of today’s foremost composers including Wolfgang Rihm, Johannes Maria Staud, Friedrich Cerha, Toshio Hosokawa and Matthias Pintscher. They also regularly appear with chamber music partners like Nils Mönkemeyer, viola and Sebastian Manz, clarinet. In 2011, the trio started its own concert series, the Boulangerie, in Hamburg and Berlin. At every one of these concerts, a classical composition is performed alongside a piece of contemporary music. The composer of the contemporary work is always present at the concert and talks with the three musicians about his or her oeuvre.

The range of the Boulanger Trio’s wide repertoire has been documented on five CDs: their latest recording of works by Ludwig van Beethoven was released in July 2014 on Hänssler Profil and has already won Pizzicato magazine’sSupersonic Award. It features alongside the Trios in G major Op. 121a, “Kakadu Variations” and B-flat major Op. 97 “Erzherzog”, the Trio Movement in B-flat major WOO 39. Also released on Hänssler Profil were the 2012 CD with compositions by Dmitri Shostakovich and Peteris Vasks, which was also awarded a Supersonic, and the 2011 recording of works by Johannes Brahms, Franz Liszt and Arnold Schoenberg, which won the Excellentia Award in Luxembourg. Two earlier recordings featuring works by Robert and Clara Schumann, Camille Saint‐Saëns, Gabriel Fauré, Wolfgang Rihm and the German first recording of Lili Boulanger’s works appeared on the label ARS Produktion.

The ensemble is named after the sisters Nadia and Lili Boulanger, whose exceptional personalities and uncompromising devotion to music continue to be a great source of inspiration to the trio.

This album contains no booklet.