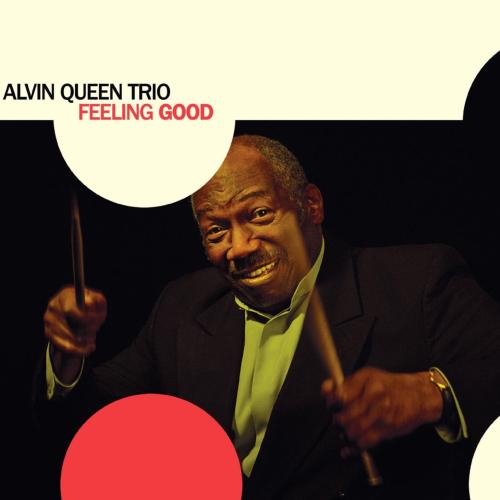

Feeling Good Alvin Queen Trio

Album info

Album-Release:

2024

HRA-Release:

14.06.2024

Album including Album cover

- 1 Out of This World 06:01

- 2 It Ain't Necessarily So 04:09

- 3 Waltz for Ahmad 03:38

- 4 Bleecker Street Theme 06:40

- 5 Love Will Find a Way 04:00

- 6 The Night Has a Thousand Eyes 05:35

- 7 Spartacus Love Theme 03:39

- 8 Feeling Good 03:51

- 9 Firm Roots 05:04

- 10 Send In The Clowns 03:23

- 11 Falling In Love With Love 05:59

- 12 Someone to Watch Over Me 03:43

- 13 Three Little Words 06:00

Info for Feeling Good

Alvin Queen is reported as saying that for all their excellence he’d rather not record with celebrity jazz stars. Instead, intent on leaving egos at the door, he prefers to work with relatively unknown musicians that deserve wider attention. An admirable stance, though it’s saddening to realize that interesting star line-ups, that most everybody in the jazz realm will be able to imagine, will never see the light of day. The last half decade, Queen has stayed true to his words and released two Oscar Peterson tributes with bright young lions from Denmark and Sweden.

Here’s another one for the books. Drum legend Queen, whose life story reads like a jazz fairy tale, chronicled among others by Flophouse in two parts here and here, assembled pianist Carlton Holmes and bassist Danton Boller. No stars perhaps but, mind you, guys with impressive credentials. Holmes is an experienced musician that played with a diversity of greats as Lionel Hampton, Freddie Hubbard, Branford Marsalis and Diane Reeves. Boller was a pinnacle of Roy Hargrove groups and cooperated with Mulgrew Miller, Ari Hoenig, Steve Nelson, Robert Glasper, among others.

An excellent pairing. Whether the music is like stormy or sunny weather, or sweet or peppery soul food, the trio’s playing is marked by uncommon airiness. Jazz in its purest form, a mix of swing, melody and interaction, needs to breathe and Queen & Co, three guys that interact like kids jumping on a trampoline, know it all too well. Holmes’s touch is subtle and his lines flow gracefully from head to tail, abetted by the solid and lyrical bass playing of Boller and by Queen, Mr. Precision, dynamic and always a servant of the song and the ideas of his fellow jazz cats.

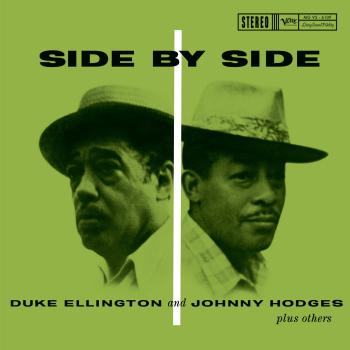

He’s still only 73, but it seems as if he’s been around forever. That’s because Alvin Queen was barely thirteen when Elvin Jones took him under his wing and he never looked back, a shoeshine boy on the streets of Manhattan that migrated to Geneva, Switzerland and the fruitful jazz realm of Europe, mingling with giants like Ray Brown, Sweets Edison, Guy Lafitte, not least enriching the classic piano trio format with Oscar Peterson and Kenny Drew.

It’s all the more fitting that Queen included Out Of This World and The Night Has A Thousand Eyes, classics that have arguably been re-invented most imposingly by the John Coltrane Quartet, with Elvin Jones behind the kit. Queen’s vivid cross rhythms and driving rolls markedly take those two standards to the next level. The former’s light-footed bossa coda is a nice touch.

Diversity and re-invention is key. Oldies like It Aint’ Necessarily So are turned into a shuffle, Someone To Watch Over Me into a lovely solo piano piece, contrasting nicely with an epic, impressionistic take on Send In The Clowns. Holmes adds a touch of mellow synth on Love Will Find A Way, taken from a 1977 album by Pharaoh Sanders. The meaty, Latin-tinged version of Feeling Good makes everybody happy no doubt, as will Cedar Walton’s Firm Roots, that starts with a stunning drum intro, mixing Afro-tones and Billy Higgins in thunderous fashion.

As you may have noticed, interesting repertoire. Brought back to life outstandingly by the latest installment of the Alvin Queen Trio.

Carlton Holmes, piano, synthesizer

Danton Boller, bass

Alvin Queen, drums

Alvin Queen

was born on August 16, 1950, in the Bronx, New York, but his family relocated to Mt. Vernon when he was 2 years old. The Queens were poor, but the Levister Towers Projects, where Alvin grew up, proved to be rich territory, as he was surrounded by many individuals who, like him, sprouted into the leading exponents of their generation.

There were scores of musicians, like sax men John Purcell and Jimmy Hill; vibraphonist Jay Hoggard; pianist Tommy James; B-3 organ champ Richard Levister; his swinging brother, Millard Levister on drums; and far too many others to name. And Alvin's list of celebrity running mates didn't end with musicians; they included future NBA stars like Ray Williams of the New York Knicks and Gus Williams of the Seattle Supersonics.

Alvin's hoop skills, however, were limited to the neighborhood courts, where he'd go head-to-head at the infamous Fourth Street playground with other wannabe hardwood stars, which included future Academy Award winner Denzel Washington. In fact, it was Denzel's father, Elder D. Washington Sr., who was pastor of the First Church of God In Christ, where Alvin's grandmother was a member. That church ended up playing a pivotal role in Alvin's life, because it's where he got his first dose of spirit-filled music, and -- after he began singing in the choir and playing the tambourine - it's where he began connecting with and conveying the rhythms of his life.

Alvin was introduced to the drums at an early age by his brother, Willie Queen, who was a standout percussionist at with the Grime School Marching Band. It was Willie who convinced Alvin that this was something he should stick with. While Christmas shopping with his mother one morning, Alvin spotted a kid playing drums in the second-floor storefront window of the Andy Lalino Drum Studio. At the time, Alvin had been earning some change shining shoes, but dreams of pulling together enough money to get his own drum set were just that - dreams.

But while shining shoes wouldn't get him the money he needed, it did give him an excuse to meet the studio owner. So one day, Alvin, shoe shine kit in hand, wandered up the stairs of the studio and asked Andy Lalino if he wanted a shine.

That’s how it all began. “You know anything about playing drums?” Andy asked.

“Well, I play for the Grime School Marching Band, and I’d love to play your drum set,” Alvin replied.

“OK, then have your mother give me a call,” he said.

Alvin’s mother contacted Lalino and Alvin started lessons. But money was tight, and the lessons were one of the first things that had to go.

Fortunately, though, Andy decided to keep Alvin around the studio for odd jobs and an occasional shine.

Free lessons were a bonus.

Alvin was introduced to jazz at an early age. Every Saturday, his father would take him to Harlem to have his hair done at Sugar Ray Robinson’s barbershop. Afterward, he’d take Alvin to the Apollo to catch a show before heading back to Mount Vernon. He’d see such lions as John Coltrane; the Cannonball Adderley Quintet, featuring Nancy Wilson; and Ruth Brown, who would end up giving Alvin one of his first professional gigs.

During the early ’60s, there were many places to check out jazz in Mount Vernon, too. The city might have been only four square miles, but there were at least eight clubs in the tiny town.

In fact, it was in Mount Vernon that Alvin played his first date. It was at a club called the Ambassador Lounge, with the Jimmy Hill Trio, featuring Richard Levister.

The drummer couldn’t make the date at the last minute, and Jimmy Hill came to Alvin’s parents’ home to see if Alvin could help out. Alvin was just 11 years old, and the only way he could get in was to be escorted by an adult. But Alvin knew all the tunes, thanks to his father’s record collection, and the word was out that he was “the man,” despite his young age.

“This is how my professional music career started,” Alvin says, “Thanks once again to people like Jimmy Hill and Tina Sattin, who helped out so many kids in the Westchester area, working with us through the YTI in Yonkers, to keep us on the right track.”

That same year, it was Andy Lalino who escorted Alvin to the original Birdland on 52nd street for the annual Gretsch Drum Night.

Andy seated his student right next to an all-star lineup of drummers: Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, Mel Lewis, Charlie Persip and Max Roach. And after Alvin played, they all poured accolades on the young prodigy for his performance.

A year later, Alvin did his first recording at the age of 12, but the recording was never released. Joe Newman was the contractor and musical director; the musicians included Joe Newman on trumpet; Zoot Sims on tenor sax; Art Davis on bass; Hank Jones on piano, on only one side; and Harold Mabern, playing piano on the other side.

Despite the whirlwind of musical opportunities that had come Alvin’s way up to that point, he sees the following year, 1963, as the “big night” in his early jazz experience. That’s when John Coltrane was performing at Birdland, and Alvin happened to be on hand for the recording of the now-famous “Live At Birdland” album, featuring the tune Afro Blue. Elvin Jones sat Alvin at the front table – “under the drums” – next to Elvin’s wife.

“Elvin started the set out with John and played a few numbers,” Alvin remembers. “Then he said the kid has to learn this stuff, and he put me up on the drums. It was the greatest opportunity of my life, to sit in with the great John Coltrane!”

During this time, Alvin was still shining shoes to keep some change in his pocket. But his sidewalk business played a much more important role than financial: It allowed him to stay in touch with the musical giants of the era, as he buffed the shoes for the likes of Blakey, Ben Webster, and Thelonious Monk.

But Alvin’s reputation far surpassed his prowess as a shoeshine man. By age 15 he began to frequent the various Manhattan jam sessions in nightclubs and lofts. There was the Doom, across from the Five Spot Café on St. Mark Street, where he’d meet up with Tony Scott, Walter Bishop, Jr., Reggie Johnson, and Walter Perkins.

There was also the famous East Side club, Slug’s, a favorite of players like Lee Morgan, J.C. Moses, and Jackie McLean, among others.

Then he’d often pop into an after-hours joint run by vibraphonist Ollie Shearer. “This is where I met Kenny Barron, Marvin Pertilo and Dick Berk,” Alvin recalls.

Alvin also started getting out of the New York area. He’d travel down to the Gracie Belmont Club in Atlantic City to work with the Wild Bill Davis Organ Trio, with Dickey Thompson on guitar. Alvin was 16. ...

This album contains no booklet.