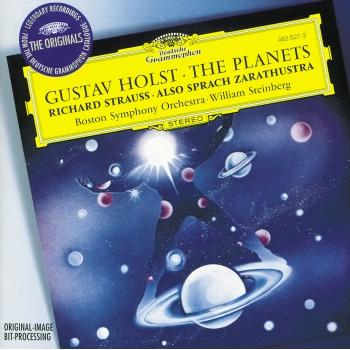

Boston Symphony Orchestra & William Steinberg

Biographie Boston Symphony Orchestra & William Steinberg

William Steinberg was clear about the future direction of his life from an early age: when he was only thirteen years old he conducted his own setting for chorus and orchestra of excerpts from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in addition to being active as a pianist and violinist. He studied piano, theory and conducting at the Cologne Conservatory, where his tutors included Hermann Abendroth, and graduated in 1919, winning the Wüllner Prize for conducting. He immediately joined the Cologne Orchestra as a second violinist, only to be dismissed by Otto Klemperer for using his own bowings. Shortly afterwards however Klemperer took him on as an unpaid assistant, and in June 1922 he conducted Halévy’s La Juive at short notice. Promoted to the post of principal conductor at Cologne in 1924, during the following year Steinberg succeeded Zemlinsky at the German Theatre in Prague; and after making his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra at the beginning of 1929 he was appointed chief conductor of the Frankfurt Opera. Here he led the first performances of George Antheil’s Transatlantic and Schoenberg’s Von Heute auf Morgen, as well as the local premières of Berg’s Wozzeck and Weill’s Aufsteig und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny. In addition he appeared regularly in Berlin at the Staatsoper.

As a result of the assumption of power by the Nazi party in 1933 Steinberg was sacked from his post in Frankfurt, but was permitted to conduct for the Jewish Culture League. He became chief conductor of the Berlin branch of this organization in 1936, the year in which he managed to leave Germany, travelling to Palestine by way of Antwerp, Stockholm and Vienna, in each of which he enjoyed success as a conductor. In Palestine he took charge of the orchestra formed by his colleague the violinist Bronislaw Huberman and prepared it for concerts with Toscanini at the end of 1936, as well as conducting it from 1937: Toscanini was sufficiently impressed with Steinberg’s work to invite him to take over from Rodzinski as assistant conductor of the NBC Symphony Orchestra in New York. Steinberg first conducted this orchestra during June 1938 and broadcast with it until the end of 1940.

Helped by colleagues from Europe, such as the brothers Adolf and Fritz Busch, Steinberg soon began to gain guest engagements in America: he conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1941 and the New York Philharmonic in 1943, and served as permanent guest conductor of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra from 1944 to 1948, alongside Pierre Monteux. On Toscanini’s recommendation he was appointed as chief conductor of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra in 1945. Referring to himself during his period with the orchestra, 1945 to 1953, as ‘Buffalo Bill’, having already taken American citizenship in 1944, he recruited many players from Europe and through his relentless demand for impeccable performance he raised the standard of the orchestra significantly, as may be heard in its first recording, that of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 ‘Leningrad’.

Steinberg’s success in Buffalo established his name as a conductor of note in the USA, and in 1952 he was appointed to his most significant position, as chief conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. He remained with this orchestra effectively for the rest of his life, until 1976, and, to quote the critic Richard Freed, it was he who gave it ‘definition’. In addition to his work in Pittsburgh he also held several other important posts, as chief conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra (1958–1960), principal guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (1966–1968), and chief conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1969–1972), by which time he was already suffering from poor health.

Steinberg expressed his vision of the ideal artistic interpreter eloquently in print in 1965: ‘I think it is only he who is capable of making the work speak entirely for itself, who, besides integrity, possesses all implied spiritual traits and virtues of character which he polishes in the furnace of intuition and inspiration, and he who can muster enough modesty to hide himself from the eyes of a crowd craving to be entertained or provoked.’ As a conductor he shared the philosophy of Toscanini in that it was the conductor’s first responsibility to reveal as far as possible the intentions of the composer without any personal gloss. At his best he was held to possess an exemplary command of the baton in terms of clarity and precision and his recordings faithfully reflect his straightforward, uncluttered and deeply considered approach to performance.

For the Capitol label Steinberg made numerous recordings with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra; these included powerful accounts of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 ‘Pathétique’, as well as eloquent readings of two excerpts from Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, and Elgar’s Enigma Variations. His support for the contemporary music of his lifetime is well exemplified by his recordings of Vaughan Williams’s Five Tudor Portraits (an unusual recording taken from a live concert), Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler Symphony and the Symphony No. 3 of Ernst Toch, commissioned and first performed by Steinberg in 1955 and notable for its highly unusual orchestration, including a ‘hisser’, a tank of carbon dioxide which produces sound by the release of a valve, and a contraption filled with wooden balls set in motion by a rotating crank.

After the orchestra’s relationship with Capitol and EMI ended it made a number of excellent ‘audiophile’ recordings for the Command Classics label, several of which show Steinberg and the Pittsburghers at their very considerable best. These included the complete symphonies of Brahms, Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7, Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2, and Stravinsky’s Petrushka. During his short time with the Boston Symphony Orchestra Steinberg made a number of recordings for RCA and Deutsche Grammophon. These included typically strong-boned accounts of Holst’s The Planets, Richard Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra, and the Symphonies No. 6 of Bruckner and No. 9 ‘Great C major’ of Schubert. A vivid image of Steinberg’s character as a musician has been given by one of his players in the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra: ‘He was giving something to the people, handing it gently to them, beautifully.’