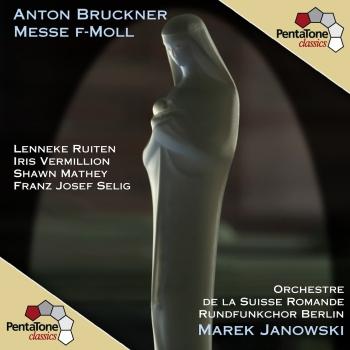

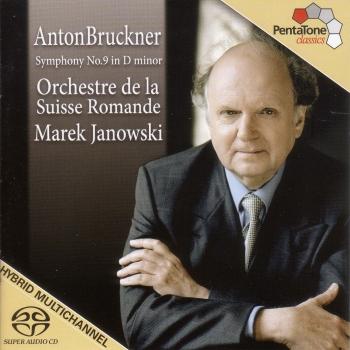

Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Nowak Edition Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2008

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

18.07.2013

Label: PentaTone

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Orchestral

Interpret: Orchestre de la Suisse Romande & Marek Janowski

Komponist: Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

Das Album enthält Albumcover Booklet (PDF)

- Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, WAB 109 (1894 version)

- 1 Symphony No. 9 in D minor: I. Feierlich, misterioso 25:08

- 2 Symphony No. 9 in D minor: II. Scherzo Bewegt lebhaft - Trio Schnell, Scherzo da capo 11:00

- 3 Symphony No. 9 in D minor: III. Adagio Langsam, feierlich 25:51

Info zu Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Nowak Edition

If one includes the F-minor study symphony dating from 1863, and the Symphony No. “0” dating from 1869, then Anton Bruckner composed a total of 11 symphonies. However, Bruckner weeded out both early works from his definite canon of symphonies, and therefore the symphony which received the conclusive number of 9 was also most emphatically his “Ninth”. His “farewell” work. Principally due to the legacy left by Beethoven, the term “Ninth” made him overly feel awkward, perhaps even somewhat fearful. Otherwise, it is impossible to explain why Bruckner laid aside his work on the Symphony No. 9 so shortly after beginning with such commitment, and consciously turned to other projects.

On August 10, 1887, Bruckner had completed the composition of his Symphony No. 8, and had immediately and vigorously dived into his No. 9. However, after receiving the crushing verdict of Hermann Levi on his Symphony No. 8, the première of which he was planning to give in Munich, Bruckner began work, full of feelings of guilt (“Ich Esel!” = “What a donkey I am!”), on a significant revision of the C-minor symphony. However, even following the conclusion of the new version, he did not continue work on his Symphony No. 9. Instead, Bruckner undertook first a fundamental revision of his Symphony No. 3 and then of his Symphony No. 1. Finally, in 1890 he also revised his Symphony No. 2 before allowing it to go into print. Not until February 1891, did Bruckner again start work on his ninth. He wrote as follows to Theodor Helm: “I have begun work on my Symphony No. 9 (in D minor).” Begun? For well-nigh four years, the first draft had been lying in his drawer. Was he trying to keep quiet about the lengthy, deliberately chosen break in the creative process?

It took Bruckner until Christmas 1893 to finally complete the first movement of the Symphony No. 9 – six years after penning the first sketches and ideas. The many years spent by Bruckner struggling with his Symphony No. 9 prove that it was definitely up-hill work for him. No other composition ever demanded his attention and powers of creation for such a lengthy period of time. And the Scherzo, the rough outline of which he had already sketched back in 1889, also took him time. Bruckner spent the period between October 1892 and February 1894 working on this. It is interesting to note, that he needed only about nine months for the expansive Adagio. He began work on the Finale in May 1895, and the last dating on this movement was August 11, 1896. It remained unfinished. The sources that have come down to us show a movement consisting of well over 500 bars, with completely developed sections, partly finished drafts and rapidly penned sketches. During the 1990s, the Bruckner-Gesamtausgabe (= Bruckner Complete Edition) dedicated itself with increased efforts to the scientific reviewal of the sources for the final movement. But even though recent years have seen substantial performance versions and other committed attempts to complete the symphony, the work remains a “torso”. No matter how one looks at it, or how it is performed – be it as a three-movement work (as in the recording at hand, based on the Nowak-Gesamtausgabe = Nowak Complete Edition), or as a “complete” reconstruction, or with the “Te Deum” as a final movement – ultimately, all solutions turn out to be unsatisfactory.

The première of the work took place in Vienna on February 11, 1903, under Bruckner’s disciple, Ferdinand Löwe. He conducted his own version of the work, using the “Te Deum” as the Finale. Not until 1932 did the première of the original version take place in Munich, under conductor Siegmund von Hausegger.

By the time he wrote his Symphony No. 3 (likewise in D minor), Bruckner had completely refined the model for his symphonic works. He had been accused of schematism, simplicity. An unpleasant rumour was put about suggesting a single symphony, which he had “composed” nine times. This accusation can be countered. In his attempts at “arranging” his symphonies, Bruckner worked like a chemist, mixing up all ingredients at his disposal in order to create something new. And thanks to his outstanding training in musical theory, Bruckner had an infinite amount of material at his fingertips. Therefore, his symphonies are nothing more than a chemical process which, while constantly repeating itself, is ever more intensively refined, modified and sublimated, and which already senses its goal – the synthesis – during the first attempts, and later truly knows it. Bruckner’s outlining of a symphony remains steady and constant, yet the inner structure changes from work to work. Neutrally speaking, this phenomenon of the apparent symphonic similarity could be defined as the “reinterpretation of an original model”. However, this “work-in-progress” character – i.e. the constant reworking of form and content – is not exclusively demonstrable in the series of symphonies as individual works, it also forces its way into the actual core of the works.

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 is a summary of this “work-in-progress” strategy, yet simultaneously it is also a preview of what would have been – not only had he completed the Finale, but also had he composed a tenth symphony. Bruckner had never written so modern a work as his Symphony No. 9, no other composition of his plunges harmonically so deep into the 20th century. Bruckner had never been so innovative as in the beginning of the first movement, the resolution of which surpasses even his own symphonic model.

The first theme, which was usually clearly laid out and formulated, does not appear at the beginning of the work. On the contrary, the listener witnesses the evolution of a theme derived from the nucleus of the note “d”, which is exposed in an 18-bar pedal point. From this also evolve the basic intervals of a third and a fifth. Suddenly, the “d” is split into the neighbouring notes of “d flat” and “e flat”. The harmony is weak, the few attempts at melody searching. Everything is striving towards the outbreak of the first theme: a unison plunging down over two octaves, like the original musical explosion. The development is calmed down only by a general pause, after which the second theme, long drawn out and lyrical, is slowly allowed to develop. There could not be a stronger contrast. The exposition is concluded by a march-like third theme group. In the development, the first theme interrupts again into the foreground. The recapitulation enters almost imperceptibly, drawing a veil over the actual beginning. The coda does not present, as usual, the majestic apotheosis, but accentuates in its emphasis on the open fifth the catastrophic, nervous character of the entire movement. Neither is the first theme, which was destroyed in the development, the object of contemplation here.

The Scherzo is probably the most modern (and perhaps also most inspired?) piece of music ever written by Bruckner. Its harmonic ambiguity, its incessantly hammering rhythm has been interpreted as a harbinger of the “machine world” of the 20th century. Bruckner as the Austrian harbinger of Shostakovich? Here, nothing is jocular or bucolic. And how does the “elfin romanticism” of the F-sharp major Trio fit in with this manic din? Not in the slightest: the disturbance of a new era also clings to this trio.

Bruckner’s last completed symphonic movement – the Adagio – consists of five sections. However, this is only how it is penned in the score. The permanent structural changes in the themes themselves cover up the traditional form criteria. One could easily describe, and also interpret, this movement as an autobiographically motivated composition. During the months in which he was working on the movement, Bruckner had more or less withdrawn from public life. A parting which was certainly painful to him. And this highly expressive movement is equally filled with pain, written in an individually subjective manner. The ninth interval at the beginning opens up an enormously expansive area, the basic key of E major is almost repealed. The chorale-like “Abschied vom Leben” (= farewell to life), as Bruckner himself described the episode in horns and tubas, leads into the song-like segment (with quotes from the “Gloria” in Bruckner’s own D-minor Mass). The themes mentioned are then further elaborated in tremendous strokes of intensification, modified and brought to gigantic climaxes. It would be hard to find the equal of such intensity of expression and monumentality in the history of music. At the climax, the initial motive breaks through, and the music ends abruptly, as if with an enormous outcry. After that, all that follows is peace and tranquillity in E major.

“The fact that it stands up well is attributable to the quality of the playing as much as to Janowski’s interpretation, which is responsive to the symphony’s long drawn-out paragraphs as well as the need for weight in the climaxes. It is a performance that breathes in terms of movement and in the airiness of its sound. Pentatone’s recording aims for clarity, and brings out much detail that gets lost in Brucknerian mud.” (The Telegraph)

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Marek Janowski, conductor

Keine Biografie vorhanden.

Booklet für Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Nowak Edition