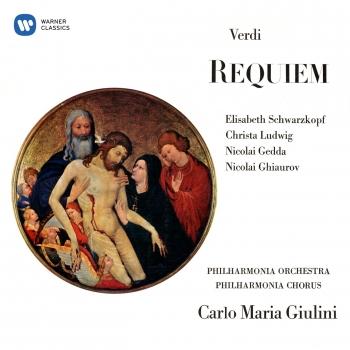

Verdi: Messa da Requiem (Remastered) Philharmonia Orchestra, Philharmonia Chorus & Carlo Maria Giulini

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2020

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

14.02.2020

Label: Warner Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Vocal

Interpret: Philharmonia Orchestra, Philharmonia Chorus & Carlo Maria Giulini

Komponist: Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

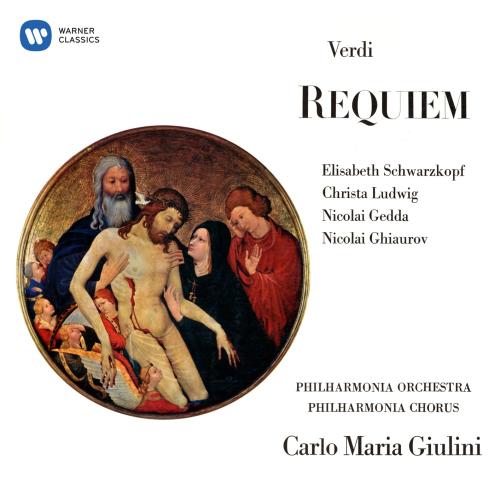

Das Album enthält Albumcover

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Giuseppe Verdi (1813 - 1901):

- 1 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: I. Requiem 05:36

- 2 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: II. Kyrie eleison 03:54

- 3 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: III. Dies irae 02:10

- 4 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: IV. Tuba mirum 03:04

- 5 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: V. Liber scriptus - Dies irae 05:08

- 6 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: VI. Quid sum miser 03:52

- 7 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: VII. Rex tremendae 03:58

- 8 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: VIII. Recordare 04:17

- 9 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: IX. Ingemisco 03:49

- 10 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: X. Confutatis 05:30

- 11 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XI. Lacrymosa 06:35

- 12 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XII. Domine Jesu Christe 04:53

- 13 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XIII. Hostias et preces 06:03

- 14 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XIV. Sanctus 02:46

- 15 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XV. Agnus Dei 05:20

- 16 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XVI. Lux eterna 06:48

- 17 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XVII. Libera me - Dies irae 04:51

- 18 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XVIII. Requiem aeternam 02:57

- 19 Verdi: Messa da Requiem: XIX. Libera me 06:03

Info zu Verdi: Messa da Requiem (Remastered)

"The problem with recordings of this age is that they do not seem old enough to warrant the allowances we make for material derived from 78s and early mono LPs, but nor do they always entirely satisfy. More than actual distortion, of which there are only occasional traces as the choral sopranos ascend to fortissimo Bs and Cs, there is a certain woolliness about the sound, and the stereo images suggests that orchestra and chorus were not in their usual positions but just scattered around the studio anywhere. The slightly earlier recording of the Four Sacred Pieces is actually a little clearer. I don't want to give the idea that the sound is really bad, but it may not have helped my reactions to the performance.

Over the years generations of great Verdi conductors have demonstrated that performances of his works need that untranslatable word slancio together with a firm rhythmic groundswell which carries the music inexorably forward even over the longest dramatic span. For many, Giulini is among the great Verdi conductors, and here there are many marvels of lovingly shaped phrasing (and he is fortunate in having soloists who can sustain his slow tempi with absolutely no sign of strain). But for me the whole thing flounders because there is not the necessary rhythmic grip to hold it up. And when a performance lasts about 15 minutes longer than the norm this has a cumulative effect not evident when listening to individual sections. As one longer-than-usual movement follows another tension is dissipated and a boredom sets in which all Giulini's sincerity and inner conviction cannot alleviate.

Turn to another classic performance, the 1954 Fricsay, and hear how the Lacrimosa, for one, surges powerfully onward with no hint of haste while Giulini's gets bogged down by the heavy spelling out of the accompanying chords. And go where you will with your comparisons, it's the same story in every movement. Fricsay hasn't quite such good soloists (fine though they are, especially Maria Stader) and the mono recording distorts at climaxes, but the sound picture is clearer." (Christopher Howell, MusicWeb International)

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano

Christa Ludwig, mezzo-soprano

Nicolai Gedda, tenor

Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass

Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano

Philharmonia Chorus

New Philharmonia Orchestra

Philharmonia Orchestra

Carlo Maria Giulini, conductor

Digitally remastered

Carlo Maria Giulini

was born in Barletta, Southern Italy in May 1914 with what appears to have been an instinctive love of music. As the town band rehearsed he could be seen peering through the ironwork of the balcony of his parents’ home, immovable and intent. The itinerant fiddlers who roamed the countryside during the lean years of the First World War also caught his ear. In 1919, the family moved to the South Tyrol, where the five-year-old Carlo asked his parents for "one of those things the street musicians play". Signor Giulini acquired a three-quarter size violin, setting in train a process which would take his son from private lessons with a kindly nun to violin studies with Remy Principe at Rome’s Academy of St Cecilia at the age of 16.

Giulini’s studies lasted the best part of ten years, during which time he played the viola in Rome’s celebrated Augusteo Orchestra under several great conductors (De Sabata, Kleiber, Klemperer, Walter, Richard Strauss) and one or two truly dreadful ones ("Stravinsky! My goodness! He was a disaster…"). He was also a chamber musician, playing string quartets in a repertoire which stretched from Haydn to Bartók, he developed what he termed ‘the moral discipline’ of music-making as part of an ensemble.

In an interview in 1971, he said: "Perhaps because I am a viola player, I think the inside string parts are particularly important. To me the other instruments give you the physiognomy of the music; but for its bones, its inner structure, you must look to the inner parts. I also believe that melody holds the key to what the composer has to say. I agree with Toscanini that the melody must always be absolutely clear, since you should assume that, in theory, the audience is hearing the music for the first time."

Giulini’s debut concert in Rome in the summer of 1944 ended with Brahms’s Fourth Symphony, one of an inner core of ‘classic’ works that gave sinew to a consciously selective repertoire which also included choice specimens of Italian Baroque and Italian contemporary music, and such engaging ‘rarities’ as Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony. In 1950 he formed the Orchestra of Milan Radio, with which he conducted a number of rarely heard operas by leading composers: Haydn’s Il mondo della luna, Rossini’s Il Signor Bruschino and Verdi’s Attila. The following year he made his theatre debut conducting Verdi’s La traviata in Bergamo. Renata Tebaldi sang Violetta on the opening night and the relatively unknown Maria Callas sang the remaining performances.

Working with Callas and the distinguished film and stage director Luchino Visconti on La traviata in Milan in 1955 was the high point of Giulini’s early career. As he put it: "Visconti was steeped in music. He knew the difference between the straight theatre and opera: that in Verdi’s Otello it is Verdi who is interpreting Shakespeare, not the theatre director." That same year Giulini made his British debut conducting Verdi’s Falstaff at the Edinburgh Festival, after which he travelled to London for a week of recording with the prestigious Philharmonia Orchestra. In the event, the hyper-meticulous Giulini managed to complete just one work, Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. The orchestra’s founder, legendary EMI producer Walter Legge, who had been away in Italy, was furious, though the critical acclaim which greeted Giulini’s orchestrally luminous accounts of Bizet’s Jeux d’enfants, Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite and Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony – all recorded the following autumn – went some way to assuage his anger.

Words such as ‘gentlemanly’ and ‘elegant’ were often used to describe the tall, handsome, infinitely courteous Giulini: words suggesting not glibness, but mannerliness, taste and moral integrity. A devout Catholic whose repertoire included an unusually high proportion of sacred works, he declined to conduct music which lacked a ‘human’ dimension. A great Verdian, he ignored the operas of Puccini; a virtuoso interpreter of Falla and Ravel, he had little time for the music of Respighi.

His 1958 Covent Garden debut in a new production of Verdi’s Don Carlo, directed by Visconti, was a sensation. The following year, also in London, he made a recording of Mozart’s Don Giovanni which remains unsurpassed to this day. Sadly, when a new generation of ‘progressive’ theatre producers emerged in the late 1960s, he turned his back on live opera, though he did go on to make memorable recordings of four of Verdi’s greatest operas: Don Carlo, Rigoletto, Falstaff and Il trovatore.

Opera’s loss was the concert hall’s gain. In 1969, he became principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. An unhappy spell as chief conductor of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra gave way in 1978 to six fruitful years as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where his assistant was the young Simon Rattle. At the same time, Giulini formed a close relationship with the Vienna Philharmonic, with whom he recorded late Bruckner symphonies in performances of breadth, nobility and rhythmic power. As with his conducting of an earlier love, Franck’s Symphony in D minor, these were readings rich in spiritual understanding.

In his later years, Giulini worked with the La Scala Philharmonic in his home city of Milan and with a number of youth orchestras. One of his last concerts, before his retirement in the summer of 1998 aged 84, was with the Spanish Youth Orchestra. Revered by the music-going public and honoured among musicians, he celebrated his 90th birthday in May 2004 and died on 14 June 2005.

Dieses Album enthält kein Booklet