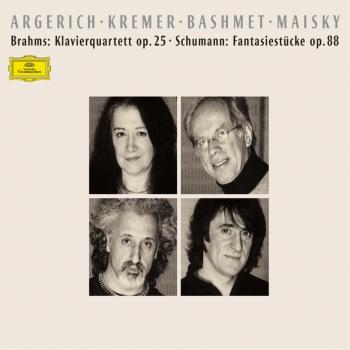

Argerich / Bashmet / Maisky / Kremer

Biography Argerich / Bashmet / Maisky / Kremer

Argerich, Kremer, Bashmet and Maisky in the Recording Studio - Summit Meeting in Berlin

On the evening of 16 November 1861, a lady and three gentlemen met in Hamburg, the birthplace of Johannes Brahms. The purpose of their coming together was the public première of the composer's Piano Quartet in G minor. The lady in question, who played the piano part, was Clara Schumann. She was accompanied by Messrs. Böie, Breyther and Lee.

On the evening of 23 February 2002, an entirely analogous constellation appeared in the Teldex Studio in Berlin: Martha Argerich, Gidon Kremer, Yuri Bashmet and Mischa Maisky met to record the above-mentioned Piano Quartet - a musical as well as an organizational challenge. A musical one, because a line-up of four world stars is in itself no guarantee of an exceptional recording - in practice, it is often the case that three members of a string quartet are joined by a pianist to conquer the piano quartet literature. An organizational one, because the pitiless engagement diary of four virtuosi in demand everywhere had to be coordinated. This feat had already been accomplished once before by Martin T:son Engstroem when he managed not only to invite the four musicians to his Verbier Festival in 2001 but also to have all four of them actually appear. That encounter of Martha Argerich with her three musketeers took place on 29 July in the Salle Médran and became a musical sensation. The artists played the First Piano Quartet by Brahms with such intensity that it was clear to everyone: this must be recorded. A date for the reunion in a recording studio was found later: February 2002 in Berlin.

And so it was that in Berlin on Saturday, 23 February the first recording session took place - exclusively devoted to musical and technological fine-tuning. By late evening everyone feels armed for the next day. The first movement is recorded within six hours on Sunday. On Monday it is the second movement's turn, with the actual recording, as usual, beginning at four in the afternoon. The string players spend the morning hours in their hotel rooms practising; Martha Argerich 'warmed up' at Steinway House in Hardenberg Strasse. In the Teldex Studio each day, along with the musicians and recording team, is the piano technician Serge Poulain, who has enjoyed Martha Argerich's unreserved confidence for years. Also constantly in service is one of the pianist's daughters, Stephanie, who prowls around the studio with her video camera looking for unusual angles - and finding them.

On Tuesday a winter storm is raging over Berlin, and it prevents us from leaving the hotel on schedule. It also limits the photo session to inside shots. The third movement, Andante con moto, unleashes a variety of emotions in all participants. As the other musicians make their way after a play-through to the control room a short distance away, Gidon Kremer remains seated at his music stand.

'Gidon, come and listen!', says Argerich.

'I'm staying here,' answers Kremer.

'Why?'

'Because it wasn't good.'

Whenever there are tensions - and they occur often in a recording studio, especially when artists of this calibre are involved - Mischa Maisky begins telling jokes. Today's object is 'Lenin in Poland'. The players now have a go at the third movement, then another, and another, until after five hours it too is 'in the can'. Wednesday is reserved in its entirety for the fourth movement. Agreement is reached relatively quickly as to how much 'zingarese' Brahms can take, so there's time left to play the entire quartet through once again from the top. Then the whole gang adjourns, not back to the hotel, but to an Italian restaurant where Claudio Abbado happily unwound after countless Berlin recordings and concerts. Along with the successful completion of the Brahms Quartet recording, there is another cause for celebration: Gidon Kremer's 55th birthday.

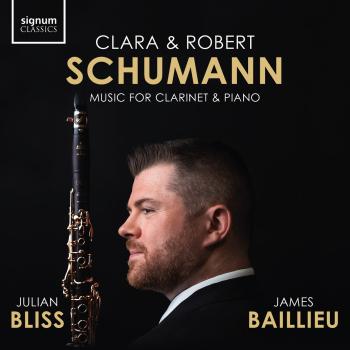

The next day Martha Argerich, Gidon Kremer and Mischa Maisky - the team that recorded Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich trios for DG (459 326-2) - come together again to record the four Fantasiestücke op.88 by Robert Schumann. Like the Brahms Quartet and the sensational Verbier appearance, this work is also linked to a pair of highly successful concerts which the three musicians gave the preceding year in Wiesbaden, Germany and Lockenhaus, Austria. The recording goes so smoothly that there is even time left to congratulate Gidon Kremer on the recent Grammy which he and his ensemble, the Kremerata Baltica, have been awarded. As far as the next Grammy in the chamber music category is concerned, one thing is certain: among the possible candidates the present CD will surely be a favourite.

(Ewald Markl, co-producer of this recording

Translation: Richard Evidon)

In Clara's Footsteps

To be the inspiration of two composers would have been enough, but Clara Schumann was more than a mere “muse”. She was a competent composer, a qualification which gave added force to her role as critical conscience to Schumann and Brahms. And she was one of the foremost pianists of the Romantic era – the trio here was written for her by her husband Robert, and she also owned the quartet by Brahms, in the sense that she presided at the keyboard in the first performance. To have this music played by a dynamic woman pianist of our own time, Martha Argerich, is therefore doubly appropriate. Robert Schumann’s little suite of four character pieces, his first essay in piano trio form, stemmed from his “chamber music year”, 1842, although it was not published until eight years later, after revision – which explains its high opus number. He began exploring chamber music for the piano with his magnificent Quintet, then decreased his number of performers for the Piano Quartet, before settling on three for his next attempt. These chips from the master’s workbench are explained by their titles and need no comment, except to point out that in giving them the generic title Fantasiestücke, a favourite one with him, Schumann was asking his performers to invest each one with a sense of fantasy. This invitation to use their re-creative imaginations is gratefully accepted by the three remarkable artists involved in the recording.

Johannes Brahms’s three piano quartets, on which he worked in the late 1850s, have differing characters. The C minor (not completed until after the others) is impassioned and concise, while the A major is equable and balanced. The G minor, everyone’s favourite, is the most varied in content. Brahms selected it for the all-important concert on 16 November 1862 at which he appeared before the Viennese public for the first time as pianist and composer. He was emboldened by the first read-through, after which the violinist Joseph Hellmesberger embraced him, saying: “This is the heir of Beethoven!” And on the day, he scored a success, as did the quartet. It is a big work which has attracted big performers: if we name only pianists who have recorded it, Martha Argerich is following such giants as Rudolf Serkin, Arthur Rubinstein and Emil Gilels. Nevertheless, it is real chamber music – one of Arnold Schoenberg’s least glorious feats was to orchestrate it, in questionable taste. Among the virtues of the present performance is that four outstanding virtuosi carry on a genuine discourse, while often operating at the outer limits of technique.

The noble opening movement is broadly conceived, with three main melodies as well as various bridge themes – Brahms, who normally husbands his resources, is here prodigal. The most extraordinary movement is the second, an “intermezzo” rather than a scherzo, its graciousness troubled by wistful harmony and an uneven 9/8 rhythm; it has a contrasting Trio. In the slow movement’s hymn-like main theme (unlike anything else by Brahms), the string players must sing and breathe as one (it helps if, as here, they come from the same tradition); a marching central section belongs mainly to the piano, before the hymn returns. The Hungarian finale – Brahms had absorbed the Magyar style through his violinist friends Reményi and Joachim – is a “gypsy rondo” which sets out with a firm stride but soon has all the instruments scurrying about. The first episode is a test of the pianist’s fingerwork (but no problem for Argerich); the first idea returns, then comes a grand, forthright second episode, followed by one featuring swooning strings which must have pleased the Viennese; the two earlier episodes are heard in turn, then there is a probing cadenza before several themes are reviewed and the opening idea returns for a dash to the finishing line. Yes, under Brahms’s dignified exterior beats the heart of a showman … (Tully Potter)