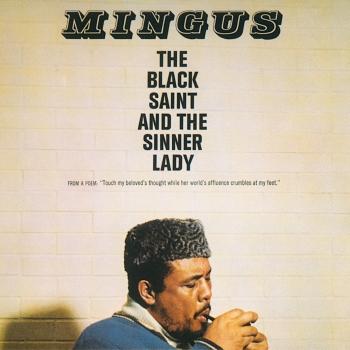

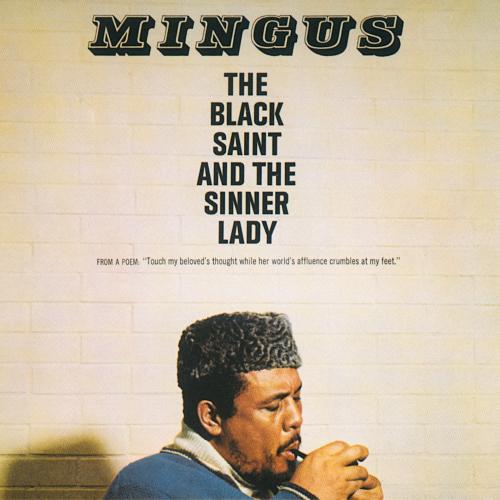

The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady Charles Mingus

Album info

Album-Release:

1963

HRA-Release:

24.09.2013

Album including Album cover

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Track A - Solo Dancer (Stop! Look! And Listen, Sinner Jim Whitney!) 06:35

- 2 Track B - Duet Solo Dancers (Hearts Beat And Shades In Physical Embraces) 06:42

- 3 Track C-Group Dancers (Soul Fusion) Freewoman And Oh This Freedom s Slave Cries 07:19

- 4 Medley Mode D-Trio And Group Dancers : Mode E-Single Solos And Group Dance : Mode F-Group And Solo Dance 18:35

Info for The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady

Ursprünglich wollte er klassischer Cellist werden. Aber es war seine Hautfarbe, die dem 1922 in Nogales, Arizona geborenen Charles Mingus diese Karriere unmöglich machte. Es blieb der Jazz, es blieb der Baß. Nach etlichen Stationen - bei Kid Ory, Art Tatum, Louis Armstrong, Illinois Jacquet - landete er schließlich im Trio des Vibraphonisten Red Norvo, das er nach dem Album "Move" wieder verließ als er bei für eine Fernsehaufnahme ersetzt werden sollte: Er war der einzige Schwarze im Trio - und Schwarze sah man nicht gern im amerikanischen Fernsehen.

Mingus, seit seiner frühesten Kindheit gegenüber Diskriminierung sensibilisiert, war dies Anlaß genug für den Bruch mit der Jazz-Szene. Er ging wieder Post austragen. Es war Charlie Parker, der ihn wieder zur Musik zurückholte - und von da an entwickelte sich Mingus zu einer der innovativsten, eigenständigsten und auch eigensinnigsten Figuren des modernen Jazz. In seiner Autobiographie "Beneath The Underdog" beschreibt er sich in drei Personen gespalten: den unbeteiligten Betrachter; "das ängstliche Tier", das angreift weil es Angst hat, selbst angegriffen zu werden. Und schließlich jener Sanfte, der sich ausnützen läßt - und der, wenn ihm das bewußt wird, zum Berserker werden kann. Mingus legte immer alles offen: er lebte seine Aggressionen und seine Neurosen unverhohlen aus - um nicht an sich selbst irre zu werden. Er galt als schwierig, cholerisch - und er wußte das. Er suchte die Konfrontation mit seinen Musikern, nicht die Harmonisierung. Und daß er dabei gelegentlich auch übers Ziel hinausschoß und handgreiflich wurde, ist hinreichend bekannt.

Mingus war sich seiner Schwächen, seiner Ausbrüche voll bewußt - er beschrieb sie fast exzessiv penibel in seiner Autobiographie. Mal verklärend, mal im Rahmen einer Privat-Mythologie, meist aber voller Ironie. Die Ironie desjenigen, der um seine Beschädigungen weiß, dem es aber nicht gelingt, sie zu ändern. Tatsächlich wäre es eine schmeichelhafte Untertreibung, Charles Mingus unberechenbar zu nennen. Wie also könnte seine Musik es sein?

Sein - formal an Duke Ellingtons Suiten erinnernde - Großwerk "The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady" erzählt von der anhaltenden Auseinandersetzung zwischen den beiden Polen Unberechenbarkeit und formaler Gestaltung. Mit seinen ständige Finten und Hakenschlägen, den überraschenden Brüchen und abrupten Stilwechseln erweckt Mingus den Eindruck des collagehaften. Tatsächlich fanden die vielen Fragmente der Aufnahme-Sessions ihre letztendliche Form erst am Schneidetisch des Produzenten Bob Thiele.

Die Musik erhält hier eine Dichte, die Mingus zuvor noch nicht erreicht hatte. Sie reflektiert einerseits all die Inspirationsquellen, die er immer wieder neu mal als Zitat, dann wieder als Stil-Pastiche hatte einfließen lassen. Blues und Gospel, der Sound Duke Ellingtons, mexikanische Mariachi-Musik, die europäische Klassik (vornehmlich der französische Impressionismus). Andererseits aber sind all diese Elemente nur Fragmente in seiner eigenen Sprache. Zuweilen ist man an die Sprache des Deliriums erinnert: eine wilde Phantasie aus an- und abschwellenden Erregungszuständen.

Kontrollierte Erregungszustände: Hier schwingen noch seine Erinnerungen an die Gospelekstasen mit, die Schärfe des Blues, die Wut des ewigen Außenseiters. Aber wie bei den Gottesdiensten der Schwarzen, so sollte auch für Mingus Musik eine gemeinschaftsstiftenden Funktion haben - er rührt an die Grundgefühle, treibt sie aber immer noch einen Schritt weiter. Dann wieder tritt - inmitten der kontrollierten Wildheit - die Form in kristalliner Klarheit zutage. Kompositionen von Charles Mingus gleichen immer kleinen Einübungen in den produktiven Selbstwiderspruch. Ganz so als wolle er sich über alles - sich selbst eingeschlossen - lustig machen, bat er seinen Psychiater Dr. Edmund Pollock, einen Text für das Album-Cover zu schreiben. Musikalischer Wahnsinn in klinischer Absegnung. Ordnungsversuche im Chaos der einander widerstrebenden Ordnungen.

"The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady" spiegelt diese produktive Zerrissenheit - jenem übermächtigen Wunsch nach vollständiger Kontrolle und gleichzeitiger, individualistischen Freiheit seiner Musiker. Mingus war berüchtigt dafür, über die Maßen zu proben. Er probte die Freiheit. Jedes Stück sollte sich bei jeder neuen Aufführung als neu erweisen. Zuweilen griff Charles Mingus auf einen Trick zurück: Statt Notenblätter zu verteilen sang er seinen Musikern die Themen vor. Sie mußten die Musik nach Gehör lernen um die sie besser zu verinnerlichen. Mingus wollte, daß sie "die komponierten Parts mit so viel Spontaneität und Soul spielen, wie sie ihre Soli blasen." Das Ergebnis: so kunstvoll die Stücke auch sind, nie klingen sie auch nur für einen Moment gekünstelt. (Harry Lachner, ARTE)

Charles Mingus, piano

Jay Berliner, guitar

Jerome Richardson, flute, soprano saxophone, baritone saxophone

Dick Hafer, flute, tenor saxophone

Charlie Mariano, alto saxophone

Richard Gene Williams, trumpet

Rolf Ericson, trumpet

Quentin Jackson, trombone

Don Butterfield, tuba

Jaki Byard, piano

Dannie Richmond, drums

Digitally remastered

Charles Mingus

One of the most important figures in twentieth century American music, Charles Mingus was a virtuoso bass player, accomplished pianist, bandleader and composer. Born on a military base in Nogales, Arizona in 1922 and raised in Watts, California, his earliest musical influences came from the church– choir and group singing– and from “hearing Duke Ellington over the radio when [he] was eight years old.” He studied double bass and composition in a formal way (five years with H. Rheinshagen, principal bassist of the New York Philharmonic, and compositional techniques with the legendary Lloyd Reese) while absorbing vernacular music from the great jazz masters, first-hand. His early professional experience, in the 40′s, found him touring with bands like Louis Armstrong, Kid Ory and Lionel Hampton.

Eventually he settled in New York where he played and recorded with the leading musicians of the 1950′s– Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Bud Powell, Art Tatum and Duke Ellington himself. One of the few bassists to do so, Mingus quickly developed as a leader of musicians. He was also an accomplished pianist who could have made a career playing that instrument. By the mid-50′s he had formed his own publishing and recording companies to protect and document his growing repertoire of original music. He also founded the “Jazz Workshop,” a group which enabled young composers to have their new works performed in concert and on recordings.

Mingus soon found himself at the forefront of the avant-garde. His recordings bear witness to the extraordinarily creative body of work that followed. They include: Pithecanthropus Erectus, The Clown, Tijuana Moods, Mingus Dynasty, Mingus Ah Um, The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, Cumbia and Jazz Fusion, Let My Children Hear Music. He recorded over a hundred albums and wrote over three hundred scores.

Although he wrote his first concert piece, “Half-Mast Inhibition,” when he was seventeen years old, it was not recorded until twenty years later by a 22-piece orchestra with Gunther Schuller conducting. It was the presentation of “Revelations” which combined jazz and classical idioms, at the 1955 Brandeis Festival of the Creative Arts, that established him as one of the foremost jazz composers of his day.

In 1971 Mingus was awarded the Slee Chair of Music and spent a semester teaching composition at the State University of New York at Buffalo. In the same year his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, was published by Knopf. In 1972 it appeared in a Bantam paperback and was reissued after his death, in 1980, by Viking/Penguin and again by Pantheon Books, in 1991. In 1972 he also re-signed with Columbia Records. His music was performed frequently by ballet companies, and Alvin Ailey choreographed an hour program called “The Mingus Dances” during a 1972 collaboration with the Robert Joffrey Ballet Company.

He toured extensively throughout Europe, Japan, Canada, South America and the United States until the end of 1977 when he was diagnosed as having a rare nerve disease, Amyotropic Lateral Sclerosis. He was confined to a wheelchair, and although he was no longer able to write music on paper or compose at the piano, his last works were sung into a tape recorder.

From the 1960′s until his death in 1979 at age 56, Mingus remained in the forefront of American music. When asked to comment on his accomplishments, Mingus said that his abilities as a bassist were the result of hard work but that his talent for composition came from God.

Mingus received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, The Smithsonian Institute, and the Guggenheim Foundation (two grants). He also received an honorary degree from Brandeis and an award from Yale University. At a memorial following Mingus’ death, Steve Schlesinger of the Guggenheim Foundation commented that Mingus was one of the few artists who received two grants and added: “I look forward to the day when we can transcend labels like jazz and acknowledge Charles Mingus as the major American composer that he is.” The New Yorker wrote: “For sheer melodic and rhythmic and structural originality, his compositions may equal anything written in western music in the twentieth century.”

He died in Mexico on January 5, 1979, and his wife, Sue Graham Mingus, scattered his ashes in the Ganges River in India. Both New York City and Washington, D.C. honored him posthumously with a “Charles Mingus Day.” (Source: www.mingusmingusmingus.com)

This album contains no booklet.