Dmitri Shostakovich's fifteenth and last Symphony has all the ingredients of Shostakovich's orchestral works, except for the participation of a choir in later symphonies, from the Russian soul capable of deep mourning to the satirical exaggeration and quotations from his earlier works and those of other composers. And yet this symphony is different from the other symphonic works of the Russian composer, who for the greater part of his life, like other composing compatriots of the former Soviet Union, had been badly treated under Stalin's regime. There is talk of bans on performances, but above all of psychological pressure, including the constant fear of being brought to death by the regime. Although the immediate danger was averted after the death of the dictator, the experiences put a lasting strain on the rest of Shostakovich's life.

During the Stalin era, the satirical reflection of political events in compositions that were partly garishly orchestrated, but above all always satirical - quite a few of the Shostakovich symphonies contain a correspondingly designed movement - proved to be a means of deriving the political pressure on the composer. Sometimes one gets the impression that the despot is more or less openly grimaced. The satirical elements of the fifteenth Shostakovich symphony, composed in 1971, seem like a posthumous lightning of the weather of grimace cutting, by which time Stalin had long been history. The desire to quote the works of other composers and his own works is also unbroken in the fifteenth. You can hear quotations from Rossini's Wilhelm Tell, from Wagner music dramas and from earlier Shostakovich symphonies. Unusual is the predominance of a cheerful over a sad mood. As a special feature, the opening motif of the first movement of the symphony corresponds to the encoding of the Russian name "Sascha": es-as-c-h-a. The symphony was premiered in 1972 by the All-Union-Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra conducted by his son Maxim.

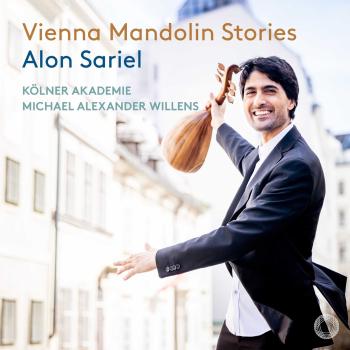

On the current album with the fifteenth Shostakovich Symphony, the Dresden Philharmonic plays under the baton of its long-time chief conductor Michael Sanderling. All the symphonies of the Russian master are now available in this line-up, which have been recorded individually in combination with Beethoven symphonies and which are now also available complete without the exciting cross-references to Beethoven. Sanderling proves to be an outstanding mediator of the Shostakovich symphonic world, who has convincingly succeeded in conjuring his orchestra to a specific, slender and clear sound, which is audibly fairer to these symphonies than some competing recordings, which are oriented towards tonal opulence. With the agreement that apparently prevailed between conductor and orchestra in the production of the Shostakovich symphonies, it can be assumed that the orchestra will experience the resignation of its principal conductor as a loss this year due to the planned cut in the orchestra's budget. Sad.

MDR Rundfunkchor Leipzig

Dresdner Philharmonie

Michael Sanderling, conductor