Cream

Biography Cream

Cream 1966 - 1968

The virtuoso playing of Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker made Cream the first band of soloists. In their two year career they brought the blues to a whole generation of white rockers and spawned legions of power trios, boogie bands and heavy metal groups...

According to rock critic Dave Marsh, Cream created “the fastest, loudest, most overpowering blues-based rock ever heard, particularly onstage.” Though they lasted only two years, Cream sold 15 million records; earned the first certified platinum album in history (for the double set Wheels of Fire); played to standing-room-only audiences across Europe and North America; and redefined the instrumentalist’s role in rock.

Indeed, the trio is often cited as the first “supergroup.” Eric Clapton’s passion and fluidity on guitar inspired a spate of “Clapton is God” graffiti in London; Ginger Baker’s brutal intensity helped create the tradition of the drum solo in rock; and Jack Bruce was one of the first bassists to introduce a jazz sensibility to a hard rock format.

Eric Clapton, born in March, 1945, was first inspired by Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and later by Jerry Lee Lewis. He quickly graduated from a plastic guitar to a real one, and from small-town Ripley to cosmopolitan London. There, he immersed himself in the nascent British blues scene, playing in the Roosters and Casey Jones & the Engineers before achieving an axemaster’s reputation with the Yardbirds and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

In the last Bluesbreakers lineup, Jack Bruce was playing bass. He left to join Manfred Mann, but not before Clapton had become excited enough by his work to want to form a band. When drummer Ginger Baker, about to leave the jazz- tinged Graham Bond Organisation, asked Clapton if he wanted to start a band, the trio became inevitable. Despite animosity between Bruce and Baker, Cream was formed in July, 1966.

They made their debut at the 1966 Windsor Festival in England, and rapidly established their legendary live style — a combination of high-volume blues jamming, extended solos and flashy instrumental showmanship.

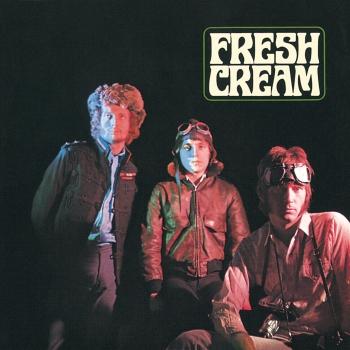

Their first album, Fresh Cream, was released in January, 1967, to moderate U.K. success. It included such chestnuts as Skip James’“I’m So Glad” and Muddy Waters’“Rollin’ And Tumblin’,” and like their live show expanded the possibilities of blues playing far beyond the traditional limits of slavish imitation. It also turned a legion of white rockers on to the sound, and in April, when it hit the U.S. charts, a host of followers — boogie bands, power trios and heavy metal groups — was spawned.

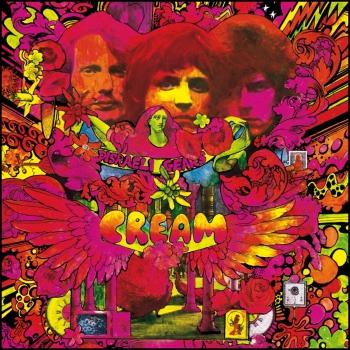

In the meantime, though, flower power, psychedelia and Jimi Hendnx were making their way across the Atlantic. Consequently, Cream’s second LP, Disraeli Gears, was filled with short, pungent rock originals drenched in fuzz-tone, wah-wah and other then-revolutionary guitar effects. It was released in December, 1967, and a few months later “Sunshine Of Your Love” reached number five on the U.S. charts. Spicy, sophisticated rockers like “Tales of Brave Ulysses” and “Swalbr” became FM underground radio staples. This was when Clapton’s comparisons to the Deity began, as he became the focus of the guitar cult that developed in the late ‘60s.

Naturally, success was accompanied by tension. Egos bloated, personalities clashed; when Bruce and Baker weren’t fighting amongst themselves — which wasn’t often — they complained of Clapton’s virtual domination of the band. There were also tensions between Clapton’s blues approach and the rhythm section’s jazz snobbery (it was almost inevitable that three overpowering improvisers would step on each other’s musical toes).

Offstage, Cream’s drug abuse was mythic. All three indulged in grass, acid and coke. Baker was using heroin heavily, and Clapton started dabbling down a road that would eventually lead him to a hard, isolated two-year heroin addiction.

Against this backdrop, Cream released Wheels of Fire in June, 1968. The album balanced short, clever songs like “White Room” (mostly written by Bruce and lyricist Pete Brown) with long blues jams like Willie Dixon’s “Spoonful” (mostly guitar workouts for Clapton).

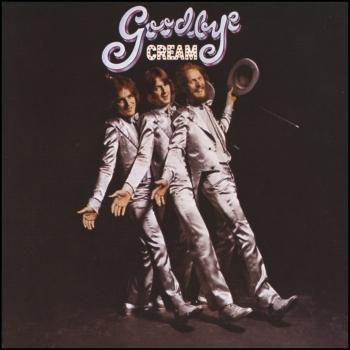

The band gave final concerts in London and New York in November, 1968. In January, 1969, they released a post-breakup collection, Goodbye, with three old and three new songs. Among the new was “Badge,” a subtle but powerfully insistent pop song with a mellotron-treated guitar section courtesy of Angelo Misterioso, otherwise known as George Harrison. A live version of “Crossroads” brought a Robert Johnson blues song to number 28 on the U.S. charts in 1969.

Jack Bruce went on to jazz experimentation, and turned up on the Golden Palominos’ recent LP, Visions of Excess. Ginger Baker discovered Africa before it got cool, and moved there. He went through two bands, isolated himself to grow olives in Italy, and was last seen bashing the hell out of a drum kit on PIL’s recent Album.

Clapton went on to sessions with the Beatles; to the short-lived Blind Faith supergroup; to being a sideman with Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett; to a solo album; and then to Derek and the Dominoes, whose double album Layla offered the most exquisitely painful guitar pyrotechnics of his career. He periodically resurfaces, most recently with Phil Collins, but few would argue that his laid-back style matches the inspiration of his work with Cream.

Ginger Baker, meanwhile, insists that Cream will never re-form. Nevertheless, in these days of post-psychedelic revival, it’s not uncommon to hear Cream down at the dance club or the rock bar, where “Sunshine of Your Love” and “White Room” are being worked into the mix, sounding every bit as fresh as ever. (by Howard Druckman)