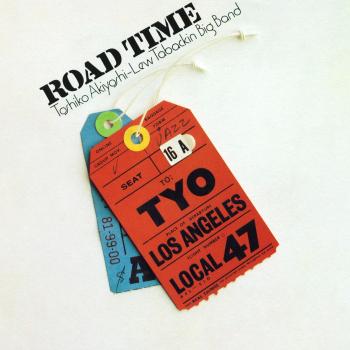

Chien Guêpe Emile Parisien

Album info

Album-Release:

2012

HRA-Release:

04.05.2012

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

- 1 Dieu m'a brossé les dents 13:48

- 2 Chocolat-citron 13:50

- 3 Bonjour crépi 05:14

- 4 Chauve et courtois 07:07

Info for Chien Guêpe

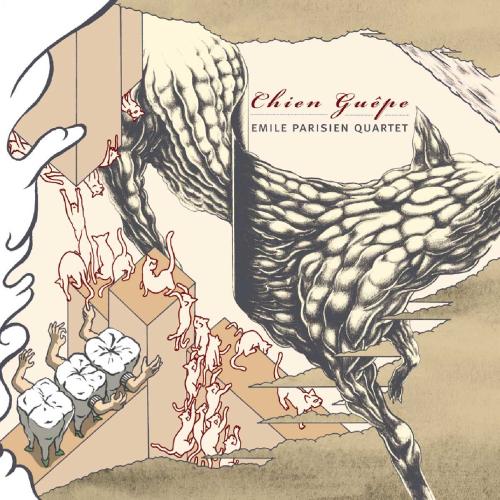

The Dadaist provocation of the cover, announcing dog but showing cat, speaks volumes about the quartet’s musical aesthetics: if humour is one of their ways of standing back, it is not the only one.

The group assume head-on the tragical and operatic accents of the themes that pass through Dieu m’a brossé les dents (God has brushed my teeth): dirges and dying voices. But from the first notes of the introduction, where the zither duplicates and bypasses the remote ringing of the piano, the drama takes on a layer of fantasy. Sitting on the edge of the mirror, we are surrounded by roaming ghosts and floating shadows. By freeing the themes from their gravity, this aesthetic choice defuses a pathos that is close at regular intervals. Paradoxically, it is when they use an extensive palette of processes, similar to cards endlessly shuffled and dealt, that the quartet reach a refined expression. The thousand shades of tones and colours contrast all the more that the piece’s structure is simple. Dieu m’a brossé les dents is a journey, an epic, with its rich movements, its breaks, its seismic rumblings, its telluric eruptions. In its climaxes, the piece rediscovers the origin of free jazz: a cry of pain against the injustice of the world. But the combustion of energy that makes the piece work carries its own exhaustion. In the ostinato that follows the catastrophe, the bells ring again and the deity of the title, ridiculous of course, can but helplessly contemplate that devastated scene. Barely good enough to make the enamel shine… So the quartet remorselessly turn their back on it and hop to a completely different atmosphere.

Chocolat citron (Lemon chocolate) opens up on the thunderous bars of some rhythmical fight. But the appearance of the piano and soprano result in reducing a little the violence of the initial beat. The sound scenery is set up: a harsh and unstructured one, and this flexible groove, as elastic as a piece of gum, delineates an organic movement reminding of the arabesques of the heated lava that stretches out in the translucent wax of the background lamps we used in the pop era. Movement and fascination: as simple as a mobile. On the surface only. In fact, the musical motifs are sharp as a razor blade. The fusion of the processes renders inoperative any distinction between what could be a matter of theme, of improvisation, of chorus, of riff, or even of rhythmic cell. Studio work imposes by nature to determine a shape, in such a way that only the narrative can be audible. Film music was mentioned about the quartet’s work, but the analogy should be extended to the imaginary of video games, of which Chocolat citron irresistibly reminds. An arcade course with its randomly multiplied obstacles, its right angle turns of scenery, its simultaneous events and its levels crossed in sudden changes of world. The first part of the piece stops swiftly. The trap closes in. The player has been caught and the boxing frenzy gives place to the dull heaviness set up by the bow of the double bass. Slowing-down, suffocation: the oxygen begins to miss, and the stridencies of a piano prepared to be ill-treated, all the more anxiety-provoking as they are irregular, provide a metallic hue to this scenery that looks like a wrecked submarine. The musical colours are finely elaborated in order to stage this no man’s time, this undecidable dusk between the abstract side of the music and its physical side, where suspense is born of a deceptive energy. Danger is lying in wait like a sniper in ambush. A few sounds, a ray of light are then enough to restart the piece. The player has found the secret passage and comes up to the surface again to fight his last lyrical battle. For the last riff will be fatal to him, and the piece will be bluntly suspended rather than completed. Game over?

Since the quartet elegantly deals with the art of self-parody, resurrection remains possible, as for the porcupine to which we had said goodbye, before he comes back as a guest star (in terminal phase though) on the cover of the second album. With Bonjour crépi (Hello roughcast), ideally placed as an interlude in the continuity of the album, the listener is on familiar ground: the ground where the miniature themes serve as a meeting point for the ludic pleasure, all the more a treat that it is free, of a necessarily free improvisation. Sound teasings, chases between instruments, rhythmical slaloms and continuous melodic events, until the end goes inevitably Bang! Aesthetics of the bumper car? At least, all the live energy of the quartet condensed into a short studio take.

Chauve et courtois (Bald and courteous) explores considerably more barren areas and the introduction all innocently asks fundamental questions: how does music come from silence? When exactly does a noise turn into a sound? The saturation of the sound space pushed forward in Bonjour crépi is replaced by a slack and mellow dilution of time which breaks up the process of orchestration of the timbres. The reverberation of the prepared zither is gradually parasited on by messy sounds. A modern, concrete, experimental music. But its merit does not come precisely from this classification: in 2012, the deconstruction and rejection of conventions are no longer original or iconoclastic. At the same time, the same old autistic and melancholic story given by the double bass works as a phrasing support for the other instrumentalists who can thus, thanks to the increasing loudness of their playing, resolve the equation of hatching and continuum. Their sounds gradually change from an interfering nature, like those that fill our everyday life, to an enchanting nature. So, before the very last bars, they logically go back into the magical box the quartet had mischievously opened, literally sucked up by the harmonics of the percussion. Eventually, the key issue of the piece is now to superimpose two kinds of beauties that never coincide on the time line, but generate a third one which makes all the price of it. In essence, beauty is not consensual. Even a stridency can be beautiful.

After the idyllic days of high spirits (the original demo recorded in 2005), the days of the assertion of a musical identity through composition (Au revoir Porc-épic/Goodbye Porcupine), the days of the freeing from influences and of the definitive acquisition of a band sound (Original Pimpant/Fresh Original), Chien-Guêpe marks an important step towards the musical horizon where the quartet direct their compass: that where energy and conviction would render invisible the level of instrumental technique, the clever use of the processes and the mixture of genres. Thanks to this genuineness, the quartet has always been able to capture the attention of an extremely diversified audience for whom, no matter what the label is as long as the music sends out Good vibrations. The quartet is bound to break down new barriers, to cross new frontiers. Say goodbye roughcast, but save the game: the return game could well smash the score. For talent-wise, God, if he exists, has well brushed those four ones. After Damien BERTRAND – January 20, 2012

Julien Touery, piano

Ivan Gélugne, bass

Sylvian Darrifourcq, drums

Emile Parisien, saxophone

Emile Parisien

The French jazz scene has a vitality, an originality and a do-it- all and do-it-anyway mentality about it right now. It is French musicians who are blazing the new trails for contemporary European jazz. There is a wonderful open-mindedness towards all musical cultures, genres and tendencies; and yet French musicians also give off the sense of having a proper grounding in their own tradition. A musician who represents all of these tendencies ‘par excellence’ is saxophonist Emile Parisien. Born in Cahors in the wine-growing region of the Lot, he is a jazz visionary. He may have one foot in that ancient soil, but his gaze is firmly fixed on the future. The leading French newspaper Le Monde has called him “the best new thing that has happened in European jazz for a long time,” while the Hamburg radio station NDR made the point of telling its listeners to give Parisien their “undivided attention.”

The reference points on Parisien’s personal musical map are very widely spread indeed. They range from the popular folk traditions of his homeland to the compositional rigour of contemporary classical music, and also to the abstraction of free jazz. And yet everything he does has a naturalness and authenticity about it. Rather than appearing pre-meditated or constrained, his music has a flow, he traverses genres with a remarkable fleetness of foot and an effortless inevitability.

What is it that makes the simple urgency of Parisien’s music quite so enjoyable? How does he manage to combine a provocative and anarchic streak with such a captivating sense of swing? Anyone who has seen and heard him on stage will know: it is because he lives his jazz with body and soul, because there is an authenticity and honesty inflecting every breath and every note.

Booklet for Chien Guêpe